Nero: Little-Known Facts About the Roman Emperor’s Reign

Written by Joshua Schachterle, Ph.D

Author | Professor | Scholar

Author | Professor | BE Contributor

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Verified! See our guidelines

Edited by Laura Robinson, Ph.D.

Date written: September 10th, 2024

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

Emperor Nero is a figure whose name has echoed through history, often conjuring images of decadence, cruelty, and tyranny. Yet beyond the lurid tales of excess and scandal, Nero’s reign is marked by a series of lesser-known facts and details that paint a more complex picture of this infamous Roman ruler.

In this article, I’ll tell you some surprising Nero facts, including his peculiar personal relationships, his unconventional pursuits, and the dark rumors and myths that followed his demise.

Biography of Emperor Nero

Nero’s birth name was Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. He was born on December 15, 37 CE in a city in Italy called Antium (modern-day Anzio). His father was Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, a Roman politician and a member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty from which the first five emperors of Rome emerged.

His mother was Agrippina the Younger, sister of the infamous emperor Caligula. According to the book Nero by Jürgen Malitz, Nero’s great, great grandfather was Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Needless to say, Nero came from an auspicious family.

The Roman historian Suetonius (69-122 CE) was clearly quite biased against Nero and his ancestors. In his book The Twelve Caesars, he wrote that Nero’s father was famous for being "irascible and brutal," and that he "enjoyed chariot races and theater performances to a degree not befitting their [family’s] position." In other words, he didn’t display the dignity and self-control thought necessary for a member of the ruling class. When Nero was born, according to Suetonius, his father said that any child born to Agrippina and himself would have a despicable temperament and be dangerous.

Nero’s father died in 41 CE, but not before being involved in a political scandal. Additionally, Malitz says Agrippina was accused of plotting a coup against the emperor Caligula. For this, she and Nero’s two sisters were exiled to an isolated island in the Mediterranean. As a result, the young Nero lost his inheritance and was sent to live with his father’s sister Domitia Lepida, mother of future Roman emperor Claudius.

When Caligula died in 41 CE, Claudius became emperor. Eight years later, Nero’s mother married Claudius. In his book The Annals of Imperial Rome, Roman historian Tacitus gives us an idea of how the emperor’s new wife was viewed by some:

In public, Agrippina was austere and often arrogant. Her private life was chaste — unless power was to be gained. Her passion to acquire money was unbounded; she wanted it as a stepping stone to supremacy.

This isn’t an objective account, of course, but at least gives us some information about how Agrippina was perceived. In Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome, David Shotter writes that Agrippina pressured Claudius to officially adopt Nero, which he did, giving him the name Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus.

When Nero Claudius turned 16, he married Claudius' daughter Claudia Octavia. In Claudius Caesar: Image and Power in the Early Roman Empire, Josiah Osgood notes that while still a teenager, Nero gave several political speeches advocating for communities who had suffered from natural disasters, arguing specifically that they should be temporarily exempted from taxes to rebuild.

Claudius died in 54 CE. While Nero’s stepbrother Britannicus had been the presumptive heir to the throne, Shotter says that in his last years, Claudius had grown more fond of Nero. Although it cannot be confirmed, many ancient historians believed that Agrippina had poisoned Claudius so Nero could become emperor.

Shotter also notes that before Claudius’ death, Agrippina had persuaded Claudius to replace two heads of the Praetorian Guard who supported Britannicus with men loyal to her. This allowed Nero to easily become the next Roman emperor in 54 CE at the age of 16.

How long did Nero reign? Ultimately from 54 to 68 CE. Roman historians Tacitus, Suetonius, and Dio Cassius, all agreed that Nero took on too many building projects during the period, bankrupting various provinces through heavy taxation to fund them.

In From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 BC to AD 68, H.H. Scullard writes that since Nero was so young, Agrippina planned to rule through her son. As a result, she had all her political rivals killed. These included Domitia Lepida, the aunt that Nero had lived with, Marcus Junius Silanus, great-grandson of Augustus, and Narcissus, a freed slave who had served Emperor Claudius.

In addition, Malitz notes that one of the earliest commemorative coins issued during Nero’s reign contained a portrait of Agrippina, rather than the more customary portrait of the emperor. However, the relationship between Nero and his mother soon began to fall apart.

Shotter writes that Nero’s “cultural pursuits and his affair with the slave girl Claudia Acte were to [Agrippina] signs of her son's dangerous emancipation of himself from her influence." Thus, when Agrippina told Nero she had changed allegiance to side with Britannicus against him, Britannicus was poisoned. Nero soon had his mother exiled from the imperial residence. He would have her killed in 59 CE.

In Nero: The End of a Dynasty, Miriam Griffin writes that after his mother’s death "Nero lost all sense of right and wrong and listened to flattery with total credulity." Tacitus agrees, saying that because of Agrippina’s absence, Nero’s behavior worsened and his tendency toward excess became more pronounced.

Tacitus also writes that Nero then divorced his wife Octavia in 62 CE, ostensibly because of infertility, and exiled her. There was a public outcry over this, so Nero then accused her of adultery and had her killed. He would go on to murder two more wives.

One of the most important occurrences of Nero’s reign was the Great Fire in AD 64, which occurred in Rome. It burned for seven days, devastating three districts and severely damaging seven more. A rumor began that Nero had started the blaze himself, and Suetonius speculated that he might have done it to clear away buildings in order to give his new palace more space.

Further legends say that he either sang a song in costume on stage during the fire or blissfully played the lyre while Rome burned (violins didn’t exist yet). There is no way to confirm any of these stories. However, Tacitus says that to divert suspicion from himself for starting the fire, Nero accused Christians of the deed.

Tacitus goes on to say that Nero had many Christians arrested and killed, adding that

Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.

While Tacitus is our only source for the story of Nero’s accusation of Christians, the majority of scholars, such as Willem Blom, believe it to be an authentic account. If so, it pertains to the history of Christianity since 4th-century church historian Eusebius wrote that Peter was crucified and Paul beheaded during this same period. Whether true or not, this would create a long, mythic history between Nero and Christians.

In 65 CE, a Roman senator named Gaius Calpurnius Piso organized a plot to overthrow Nero. According to Tacitus, someone discovered the plan and told Nero’s secretary. All the conspirators were captured and executed. Seneca, the Stoic philosopher and retired advisor to Nero, was accused of participating in the conspiracy. He denied it, but was nevertheless compelled by Nero to commit suicide.

In 68 CE, Gaius Julius Vindex, governor of a Roman province, started a revolt against Nero’s tax policy, which had increased to rebuild Rome after the Great Fire. Vindex’s rebellion failed, but one of his co-conspirators, Servius Sulpicius Galba, began to gain popular support as a possible new emperor, especially among Roman legions.

When the head of the Praetorian Guard also defected to Galba’s side, Nero fled Rome, planning to go to another province. However, he soon returned to the palace in Rome where, according to Suetonius, Nero awoke one night to find that all his guards had left the palace, leaving him completely vulnerable to attack.

At this discovery, Nero soon left the palace again, this time in disguise, accepting an invitation to stay in a villa outside the city. When he learned that the Senate had declared him a public enemy, he planned to commit suicide. However, Suetonius says he lost his nerve and asked his secretary to kill him instead. He died on June 9, 68 CE.

Lesser-Known Nero Facts

Tacitus says that In 64 CE, after having his wife murdered, Nero “married” a man, a freed slave named Pythagoras (Suetonius calls him Doryphorus). While same-sex marriages would not have been legally recognized in imperial Rome, it was at least occasionally done as a way of formally and publicly announcing one’s affections. Furthermore, in his Roman History, Cassius Dio says that in 67 CE, Nero married Sporus, a young boy.

While describing another Nero fact, Tacitus writes that from a very early age, he had been interested in writing poetry, singing, acting, and painting. He furthermore tells us that, after murdering his mother, he began to appear more and more in public, performing his artistic feats. Tacitus certainly disapproved of an emperor participating in such activities and even disdained the activities themselves as low class. He writes approvingly that since Nero’s death,

the same populace which once watched and applauded the performances of an actor-emperor (sc. Nero) has now even turned against the pantomimes and damns their effeminate art as a pursuit unworthy of our age.

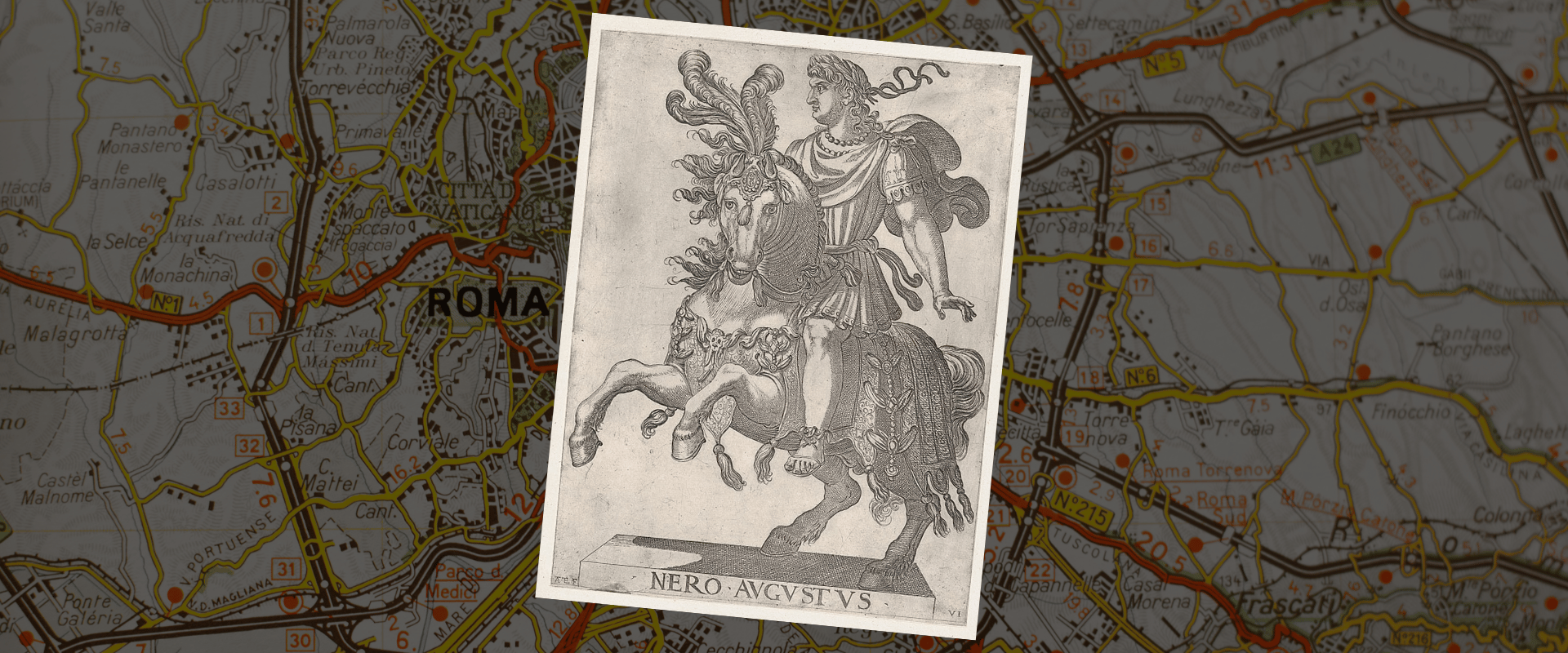

In addition to Nero’s love of poetry, singing, and acting, in The Ancient Olympic Games, Judith Swaddling writes that he also trained for and competed in the Olympic games in Greece as an athlete. Specifically, he raced chariots. In 67 CE, though the games weren’t scheduled for that year, Nero forced them to be held so that he could participate while in Greece. Unfortunately, soon after the start of the race, Nero lost control of his chariot, injuring himself and almost dying.

After Nero’s death, the so-called Nero Redivivus legend said that Nero would return to reclaim the throne. This legend continued to be believed by some as late as the early 5th century CE when Augustine of Hippo wrote of it, saying that some believed Nero “now lives in concealment in the vigor of that same age which he had reached when he was believed to have perished, and will live until he is revealed in his own time and restored to his kingdom."

This belief may have been caused by several Nero impersonators who attempted to foment rebellions during the reigns of Vitellius just after Nero’s death, Titus in 79-81 CE, and Domitian 81-96 CE. This last impersonator may have played an unwitting part in the book of Revelation, an important encounter between Nero and Christians.

Conclusion

Nero was undeniably one of the best-known emperors of Rome, although he may have been more infamous than famous. Born into a wealthy, noble family, he was officially adopted by the emperor Claudius when Nero’s mother, Agrippina, married him.

This paved the way for Nero to succeed Claudius as emperor with Agrippina pulling the strings behind him. However, eventually Nero, only a teenager when he became emperor, seems to have grown tired of his mother’s influence and banished her, later having her executed.

As an emperor, Nero was popular at first but then quickly became notorious for being prone to excess and treachery. In addition to his mother, he also murdered three wives. He was rumored to have started the Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE and then persecuted Christians to remove suspicion from himself. By the end of his life, he had burned any political bridges which might have helped him avoid being deposed and killed.