Justin Martyr: Everything About the Christian Apologist

Written by Marko Marina, Ph.D.

Author | Historian

Author | Historian | BE Contributor

Verified! See our guidelines

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Date written: October 31st, 2024

Edited by Laura Robinson, Ph.D.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

It feels like a lifetime has passed since I first chose to dedicate my professional journey to the study of early Christian history. I still vividly remember the moment I informed my professor of my decision. Young, eager, and full of ambition, I naively believed I could grasp the entirety of this vast field in just a few short years.

My professor, with a knowing smile, simply said, "You are stepping into a well of endless knowledge, filled with thinkers and writers who will change your perspective at every turn. It’s not a sprint — it’s a lifelong journey." And, as you can guess, he was right.

Among the many towering figures who have shaped the course of early Christian thought, one stands out as especially transformative: Justin Martyr.

Justin’s legacy as a philosopher turned Christian apologist offers us a glimpse into a time when Christianity was still struggling to find its place in the Greco-Roman world. His works, especially Apologies and Dialogue with Trypho, reveal the intellectual rigor and spiritual depth that defined his life’s mission.

In this article, we’ll explore the life of Justin Martyr — what we can know of his education, his conversion, and his eventual martyrdom. We’ll then turn our attention to his major writings, delving into the ideas that shaped his Apologies and Dialogue.

Finally, we’ll examine his lasting impact on Christian thought and why, centuries later, Justin remains one of the most influential figures in the history of Christianity. Join us as we enter into the time machine and work our way back to the 2nd century C.E.

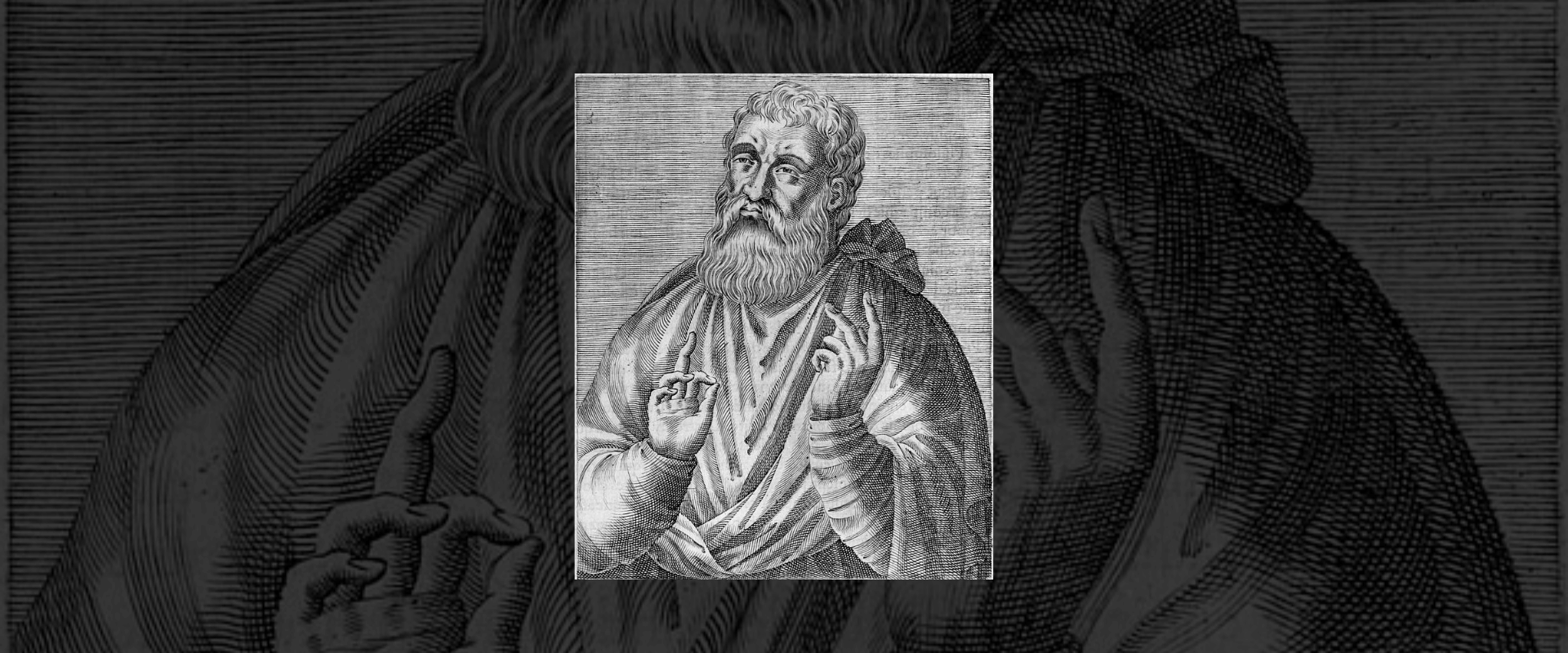

Justin Martyr: Biography

Justin Martyr, born in the early second century in Flavia Neapolis (modern-day Nablus in the West Bank), probably grew up in a Greek-speaking, non-Jewish family within the Roman province of Samaria.

In Greek Apologists of the Second Century, Robert M. Grant notes that his background suggests strong ties to Hellenistic culture, as his family bore names such as Priscus and Baccheius, evoking Roman and Dionysian connections.

(Affiliate Disclaimer: We may earn commissions on products you purchase through this page at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our site!)

Justin's early life was marked by a deep philosophical curiosity, driven by his quest for truth and meaning in a world that, at the time, offered him several competing systems of thought.

Initially, Justin explored various philosophical schools, starting with Stoicism. However, he quickly became disillusioned with Stoic teachers, finding them unwilling to engage in discussions about theology — the very subject that intrigued him the most.

His intellectual journey next led him to Peripatetic and Pythagorean teachers, but he found their approach either too focused on wealth or reliant on prerequisites he didn’t have. It wasn’t until he encountered Platonism that Justin felt he had found a system capable of addressing the deeper questions of reality and existence.

In his writings, Justin recalls how the Platonist ideas of incorporeals and the vision of God excited his mind and seemed to offer a glimpse of the ultimate truth.

The turning point in Justin’s life came during an encounter with an elderly Christian near the seashore, likely in Ephesus. The old man challenged the very foundations of Platonism, pointing out its contradictions and leading Justin to consider a higher religious authority.

This interaction ignited a new passion in Justin for the prophets of the Old Testament, whose wisdom, he realized, predated and surpassed the Greek philosophers. From that moment, Justin became a Christian, and his conversion led him to dedicate his life to teaching and defending the faith.

However, unlike some of his contemporaries, Justin didn’t become a cleric but remained a philosopher. Jörg Ulrich explains:

As a Christian, Justin did not give up philosophy, but saw himself as a Christian philosopher and thereby as a representative of 'true philosophy'. He ran his Christian school of philosophy in Rome... It is clear that he saw Christianity as a set of teachings that can both be acquired and communicated and which constantly impact one‘s specific way of life.

To avoid anachronistic projections, we must remember that Justin likely operated as a “freelance philosopher” in Rome. As Joseph H. Lynch notes in his book Early Christianity: A Brief History:

[Justin’s] school probably had no official standing with the local proto-orthodox church. His students probably included interested pagans, catechumens preparing for baptism, and baptized Christians who wanted a deeper knowledge of their faith.

This serves as a reminder of the loosely connected Christian communities — Christianities, in the plural — that existed in the capital city of the Empire during the 2nd century, a social phenomenon that scholars such as Peter Lampe have analyzed in detail.

Justin's death was as significant as his intellectual journey. Around 165 C.E., during the reign of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, Justin was arrested and tried in Rome for his Christian beliefs.

The account of his martyrdom has been preserved in three different editions. Ulrich notes that the central elements (the gist of the story) are essentially historically credible, as the process outlined corresponds to the otherwise known procedure.

The urban prefect Rusticus, who led the trial, demanded that Justin and the other arrested Christians sacrifice to the Roman gods to demonstrate loyalty to the empire.

Justin’s response was characteristically bold. When threatened by death, Justin responded with a firm belief in the afterlife: “I hope that I shall have His gifts if I endure these things. For I know that, to all who have thus lived, there abides the divine favor until the completion of the whole world.”

Rusticus, unfazed by Justin’s defiance, pressed him further, instructing him to obey the imperial decree and perform the sacrifices. Justin, however, refused, stating that no one in their right mind would trade the truth of Christianity for pagan falsehoods.

Scholarly Insights

Whose Memoirs? The Debate Over Justin’s Gospel Reference

While Justin quotes from the Gospels, he never identifies them with a specific title. Instead, he only calls them “the memoirs of the apostles.” However, in one instance Justin associates one set of memoirs to a specific apostle!

In Dialogue with Trypho chapter 106, verse 3, he writes: “And when it says that he [Jesus] changed the name of one of the apostles to Peter; and when also this is written in his Memoirs, that he changed the name of… the sons of Zebedee to Boanerges, which is ‘sons of thunder’...” This passage raises a fascinating question: whose memories Justin refer to when he says “memoirs of Him?”

Peter Pilhofer argues that Justin is referring to the Gospel of Peter, based on a plain reading of the Greek syntax and the overlap between Justin’s wording and elements found in the Gospel of Peter. Other scholars argue that Justin is referencing the Gospel of Mark, which was widely regarded in early Christian tradition as Peter’s memoirs, with Mark recording the apostle’s testimony.

The real conundrum is this: Is it possible that the only Gospel Justin mentions explicitly is the Gospel of Peter — a text later condemned as heretical, or was he referencing here the more widely accepted Gospel of Mark, associated in the early Church with Peter’s eyewitness testimony?

We invite you to explore both the Dialogue with Trypho 106.3 and scholarly debates for yourself and weigh the arguments. Does Pilhofer’s theory, grounded in syntax and textual overlap, persuade you, or do you find the traditional view convincing?

Despite the prefect’s repeated demands, Justin and his companions held firm in their convictions. They were unflinching in their refusal to sacrifice to the gods, a stand that sealed their fate. Rusticus, after having exhausted his questions, sentenced them to death by beheading.

The execution was carried out swiftly, and Justin’s calm acceptance of his death became a powerful testimony of his courage, sealing his place in the history of Christianity. Soon after his death, Justin was recognized and revered as one of the Christian martyrs and his writings continued to inspire future generations of Christian leaders and authors.

It’s precisely to his writings that we’ll turn our attention now. After all, Justin was, as Bart D. Ehrman notes in Lost Christianities, “one of the most productive proto-orthodox authors of the second century.”

Justin Martyr: Major Works

Justin Martyr's most important surviving works, First and Second Apology and Dialogue with Trypho stand as key texts of early Christian apologetics. Written in the mid-second century, these works reflect Justin’s defense of Christianity within the context of Greco-Roman culture.

First Apology

Justin’s First Apology, addressed to Emperor Antoninus Pius and his adopted sons, argues for the rationality and ethical superiority of Christianity. Central to this defense is Justin’s attempt to refute the accusation that Christians were atheists — a common charge, as they rejected the Roman pantheon of gods.

Moreover, Justin boldly proclaims that Christians worship the one true God and that, far from being dangerous, they contribute to the moral and social good of the empire by upholding virtues such as justice, chastity, and charity.

In what kind of a God does Justin believe and defend? Eric Osborn explains Justin’s views:

Christian God made heaven and earth, for he is the only God, lord, creator, and father. The Stoics say that God will be broken up into pieces when the world is made again, and Sibyl thought that everything would disintegrate, but Christians insist that the first cause, God, is above contingency.

Furthermore, Justin constructs his argument for the superiority of Christianity through a comparison with the philosophical traditions of the Greco-Roman world. He aligns certain Christian teachings with Platonic ideals, especially regarding the nature of the soul and the afterlife, while highlighting the uniqueness of Christian doctrine, such as the resurrection of the body.

For Justin, Jesus embodies the Logos, the rational principle of the universe, which was partially revealed to pre-Christian philosophers such as Socrates and Plato. However, he insists that Christianity reveals the Logos in its fullness through the incarnation of Christ.

The First Apology also includes a detailed description of Christian rituals, such as baptism and the Eucharist, emphasizing the transparency and moral integrity of Christian worship. Those values contrasted with what he viewed as the secretive and immoral practices of Roman paganism.

Second Apology

Justin’s Second Apology is often considered an extension of his First Apology, and many scholars believe the two works were originally intended to form a single document.

While the First Apology primarily addresses the Roman authorities, defending Christians against accusations of atheism, the Second Apology delves deeper into the spiritual and philosophical dimensions of Christianity, with a particular focus on the experience of Christian martyrs.

A key theme in the Second Apology is the role of demons in opposing Christianity. Justin explains that these demons, who once masqueraded as the gods of the Roman pantheon, are behind the persecution of Christians and the false accusations levied against them.

This emphasis on demonic activity reflects Justin’s broader theological framework, in which the conflict between good (embodied in Jesus) and evil (embodied in the demons) plays a central role in human history.

Moreover, by relating pagan gods with demons, Justin attacks the core of Greco-Roman religious tradition, arguing that the whole pagan mythology serves the needs of the evil forces.

Charles Munier offers an excellent conclusion regarding Justin's attitude toward Greco-Roman mythology:

Mythology, which serves as the cultural foundation of Greco-Roman paganism, provides Justin with a prime target. The apologist does not hide his deep contempt for the amorous exploits attributed to Dionysus, son of Semele, to Apollo, son of Leto, and even to Zeus himself, 'parricide, son of a parricide, overcome by the love of the most vile, most abject pleasures.' In his eyes, the diabolical origin of these tales, 'written to corrupt and pervert the youth,' is beyond doubt; this is why he sincerely pities those who believe in these legends and imagine they are imitating the gods when they give in to their passions.

Dialogue with Trypho

Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho takes a different approach, engaging in a theological debate with a Jewish interlocutor. The dialogue is framed as a philosophical discussion, but scriptural interpretation is its main focus. Justin’s goal is to convince Trypho, a learned Jew, that Jesus is the Messiah prophesied in the Hebrew Scriptures.

Throughout the text, Justin offers a Christian reading of the Old Testament, arguing that many of its prophecies — particularly those concerning the Messiah — find their fulfillment in Jesus.

The debate touches on issues such as the continued relevance of the Mosaic Law and the nature of salvation, with Justin asserting that Jesus’ coming heralds a new covenant, rendering the old law obsolete.

Although the dialogue ends without Trypho’s conversion, it is clear that Justin sees this exchange as part of a broader attempt to position Christianity as the fulfillment of Judaism — a feature that Tessa Rajak has labeled as the fundamental principle in the development of the proto-orthodoxy.

In addition to these, Justin Martyr is known to have written several other works, though most have been lost. These include Treatise Against All Heresies and a now fragmentary work against Marcion, both referenced by later writers such as Irenaeus and Tertullian.

While we lack the full texts, these writings likely expanded on Justin’s defense of Christian orthodoxy and his opposition to other forms of Christianity he labeled as heresies.

St. Justin Martyr: Historical and Theological Significance

Justin’s writings stand as monumental contributions to Christian apologetics. Sara Parvis, for instance, argued that Justin’s apologetic works served as a basic model for subsequent Christians who offered defenses to Roman authorities.

Furthermore, he provides the earliest account of Christian worship outside the New Testament, describing how Christians gather on Sundays to read the Scriptures (especially the “memoirs of the apostles”), pray, and partake in the Eucharist.

The service includes a sermon by the leader, communal prayers, and the sharing of bread, wine, and water. Collected offerings support the needy, such as orphans, widows, and those in distress, and Sunday is chosen for worship because it commemorates both the creation of the world and Christ’s resurrection.

Justin’s contributions go beyond his role as an apologist; he also played a pivotal part in shaping the intellectual identity of Christianity in its formative years. One of Justin’s most enduring legacies is his embodiment of the Christian philosopher-apologist model.

By presenting himself as a philosopher who found the ultimate truth in Christianity, Justin Martyr bridged the gap between Greco-Roman intellectual traditions and the emerging religion which was, as Michael J. Kruger noted, at the crossroads in so many of its aspects.

Additionally, Justin’s integration of Greek philosophical concepts, particularly those from Platonism, into Christian theology, allowed him to engage with educated pagans and present Christianity as the "true philosophy.”

Moreover, Justin Martyr wasn’t only a Christian apologist and intellectual; he also addressed the challenges posed by other Christian groups, such as the followers of Marcion, whom he deemed heretical. As Robert M. Royalty observes, Justin employed a rhetoric of delegitimation by linking these groups' teachings to demonic influence, thereby stripping them of the title “Christian.”

In his book La Notion d'Hérésie dans la Littérature Grecque, French scholar Alain Le Boulluec explored Justin Martyr's substantial influence in redefining the concept of “heresy.” Le Boulluec argued that it was primarily Justin who employed the notion of heresy to delineate the boundaries of what would later be called “orthodoxy,” thus imbuing the term with clear negative connotations.

But to delve deeper into Justin Martyr’s “heresiologist career” would lead us far beyond the scope of this article.

Finally, Justin Martyr and the Catholic Church share a profound connection. Within the Catholic tradition, Justin is venerated as a saint and martyr who exemplified an unwavering commitment to his belief in one God.

His opposition to Roman authorities during his trial, and his refusal to renounce his belief in Jesus even in the face of execution, have cemented St. Justin Martyr’s legacy as a powerful witness to Christian perseverance.

Conclusion

Justin Martyr’s life and works stand as a testament to the intellectual and theological development of early Christianity. As both a philosopher and a Christian apologist, he navigated the complex intersection of Greco-Roman thought and Christian doctrine, offering compelling defenses of the faith to both Roman authorities and Jewish interlocutors.

His Apologies and Dialogue with Trypho not only laid the foundation for Christian apologetics but also illustrated how deeply early Christian thinkers engaged with the broader cultural and philosophical currents of their time.

In reflecting on Justin’s legacy, it becomes clear that my professor was absolutely right – early Christian history is indeed a well of endless knowledge.

Figures like Justin demonstrate the profound intellectual richness of the period, offering perspectives that continue to influence scholarly discussions on the development of Christian thought within the broader context of ancient philosophy and culture.