History of the Bible: Timeline and Key Versions

Written by Marko Marina, Ph.D.

Author | Historian

Author | Historian | BE Contributor

Verified! See our guidelines

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Date written: September 8th, 2023

Edited by Laura Robinson, Ph.D.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

In the exploration of the history of the Bible, our journey turns towards the origins of the Hebrew Bible. Just as a previous post illuminated the layers of the Christian Bible, we now embark on a quest to unravel the intricate history of the Hebrew Bible.

The Hebrew Bible: Foundation of the Old Testament

The history of the Bible timeline finds its origins not among Christians but within the ancient Israelite community. Yet, in contemporary times, the term "Bible" often evokes thoughts of the Christian books or the New Testament.

In the Jewish tradition, the Bible is known as TaNaKh, an acronym for Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim, denoting their distinct sections. As we embark on this journey, the significance of these terms will gradually unfold before us.

Tracing the Timeline of the Bible's Origins

The Hebrew Bible emerged as the literary expression of a community-dwelling within the narrow expanse of land nestled between the ancient Babylonian (and Assyrian) empires to the east and Egypt to the west.

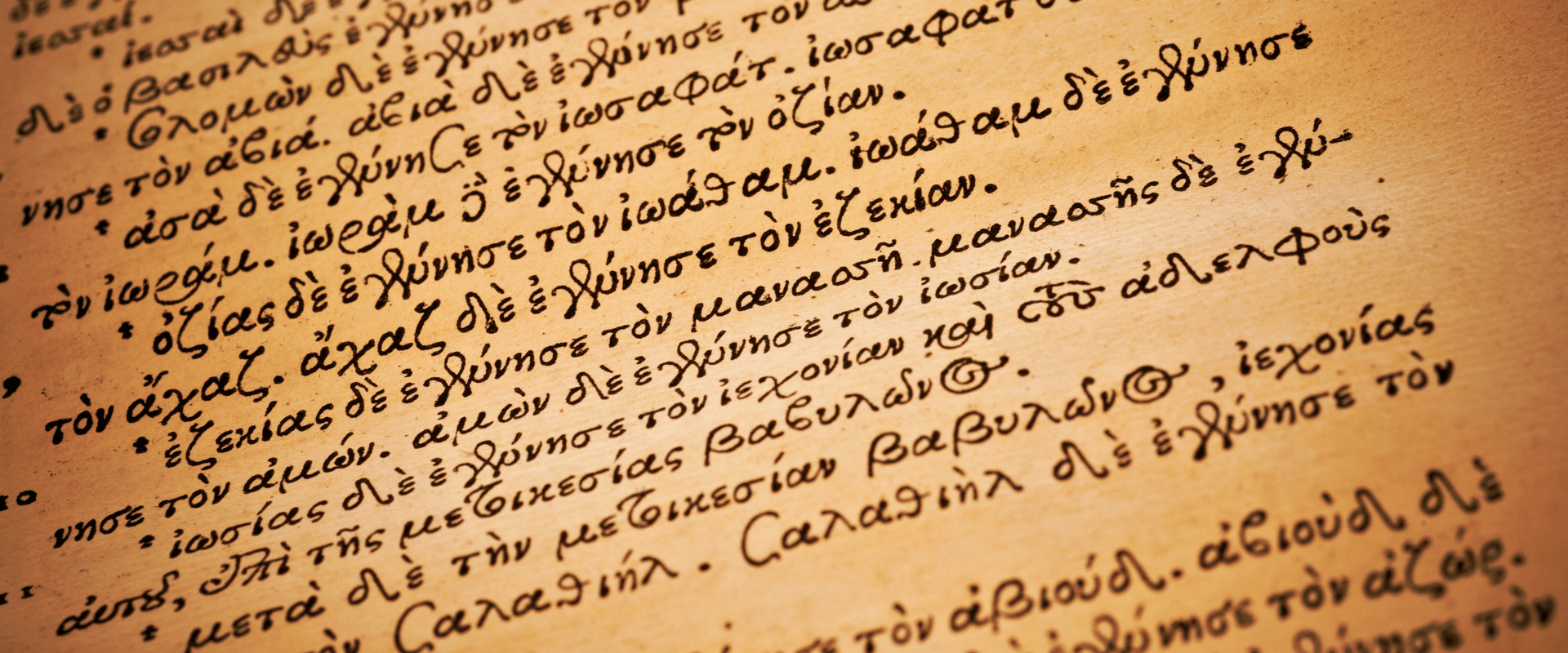

Furthermore, the original language of the Bible was Hebrew - a distinctive consonantal language with cognates in several other ancient Near Eastern languages.

Among the volumes of the Hebrew Bible, can you guess which singular book was not penned entirely in Hebrew? Resist the temptation of Google's aid – let curiosity guide your guess!

The essence of the Hebrew language unveils an intriguing connection with oral culture and heritage. Mastery of consonantal letters relied upon understanding their pronunciation. This implies that vowel sounds were perpetuated through oral transmission.

In other words, the ancient Hebrew language was a “code” intelligible only within the oral culture. But before we delve into the oral and written tradition behind the history of the Bible, we have to present its fundamental element: the content.

The Content of the Hebrew Bible: Collection of Exceptional Books

The content of the Hebrew Bible (or TaNaKh) can be divided into three categories:

- 1The most authoritative part is called the Torah, or the five books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

They provide the grand narrative of the formation of Israel as a people and the terms of its covenant with God. Exodus, for example, describes the enslavement of Israelites in Egypt, the call of Moses, the parting of the Red Sea, and the giving of God’s Law through Moses. - 2The Prophets (Nevi’im) are 21 writings that make up the second major portion of TaNaKh. They include both the historical books such as 1 and 2 Samuel and the prophetic books such as Amos, Isaiah, and Jeremiah.

- 3The 13 Writings (Ketuvim) make up the final and least internally organized portion of the Jewish Bible - making a total of 39 compositions. They include among others: Ecclesiastes, Psalms, Proverbs, Job, 1 and 2 Chronicles, and Daniel.

Please also feel free to utilize our "Books of the Bible" resource which offers a summary of all 39 books in the Hebrew Bible as well as its author, date written, theme, and key verse.

From Oral to Written Tradition:

The Bible's history entailed a fusion of oral and written methodologies. The oral aspect is particularly evident in prophetic literature and psalms. Consider the prophetic books, brimming with declarations like, "The word of the Lord came to Isiah” (Isiah 38:4) or “The world of the Lord came to me” (Ezek 13:1).

And yet we know that these oral performances that took place in the Temple (Psalms) and those of the prophets were written down at some point. Consequently, the intricate interplay between oral and written components renders the history of the Bible truly captivating.

Moreover, these compositions evolved over a prolonged span, mirroring engagement with various epochs of the ancient Near Eastern milieu. The initial texts of the Hebrew Bible were written during the 8th and 7th centuries B.C.E., while the most recent entry (the Book of Daniel) was composed in the 2nd century B.C.E.

As to the Bible’s relation with the ancient Near Eastern culture, the essay by James Greenfield highlights the persuasive influence of the Canaanite culture.

Furthermore, the creation of literature presupposes certain social settings and technical capabilities. As Karel van der Toorn observes in Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible, “being a product of the scribal workshop, the Bible owes its existence to the generation of scribes, each new one continuing the work of previous ones.”

Manuscripts: Tracing the Physical Texts

The scribal culture inevitably leads us to the world of manuscripts. After all, the Bible’s history is based on the manuscript tradition - centuries of meticulous copying of biblical books.

Did You Know?

The income of a Jewish scribe was above average in antiquity? It was a hard but lucrative business! He could earn twice as much as the ordinary worker!

The scribal culture emerged in the royal courts of the ancient Near East. It was a highly respected job only an educated minority could do. Throughout the ancient world, the production and copying of manuscripts represented an expensive process.

Furthermore, the copying of manuscripts was made more difficult because of the need for more separation between the words and sparse indicators of punctuation. Frequently, scribes confronted clusters of letters that formed words solely due to their familiar oral context.

The Transmission History of Biblical Manuscripts

Comparative scrutiny exposes a more disorderly transmission of Biblical manuscripts in Christianity than in Judaism. Within the realm of Judaism, a group of scholars called the Masoretes embarked on a mission to establish a standardized Hebrew text. It probably began in the early 2nd century C.E.

They would regulate the spelling of words and provide vowel markings and accents to the consonantal text to indicate the proper reading. The regulation of the written text through such signs probably developed most fully between 500 and 700 B.C.E.

With the so-called Aleppo Codex (c. 915 C.E.), the Masoretic text was fully standardized thus providing the common abbreviation used by scholars for the Hebrew Bible (MT).

You must wonder about the earliest surviving manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible! The oldest known manuscript fragments come from the Dead Sea Scrolls - a collection of Jewish texts that were written between 150 B.C.E. and 70 C.E.

The Canonization Process: Shaping the First Bible

The journey of Biblical canonization followed distinct paths in Judaism and Christianity, aligning with the unique trajectories of these traditions. However, before delving further, let's commence by clarifying the fundamental terminology.

Both in Judaism and Christianity, Canon represents the writings to be read in worship as authoritative religious guides. In other words, canonical books represent the Holy Bible.

The Canon formation within Judaism was shaped by two important factors:

- 1The confirmation of an internal tradition.

- 2Response to external developments.

The Confirmation of the Internal Tradition (516 B.C.E. - 70 C.E.)

During the Second Temple period, a general sense of a Canon of Scripture included three large categories of literature:

- 1Torah or the Five Books of Moses

- 2Prophets

- 3Psalms

However, the pivotal turning point was the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 C.E. Since the Temple was destroyed Judaism became even more a text-centered religion. Where would you base the sacrificial system if the Temple was gone?

Additionally, the obliteration of the Temple led to the dissolution of competing sects, leaving the Pharisees as the prevailing faction within Judaism. In essence, the Pharisees ascended as the driving influence in molding the forthcoming ethos of Judaism thus directing the history of the Bible toward their path.

External Developments: Christianity’s influence on the Hebrew Bible

A significant external catalyst that shaped the canonization of the Hebrew Bible was the emergence of Christianity. The propagation of Christianity beyond Jewish circles prompted Judaism to delineate more precise parameters for its normative faith.

Consider, for instance, the use of the Old Testament within Christian contexts. Interestingly, Christians employed the Greek translation (Septuagint) of the Old Testament to validate prophecies about the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

Nonetheless, this approach resulted in the exclusion of the Septuagint from Judaism. In fact, during the 2nd century C.E., Jewish scholars formulated three distinct Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible as alternatives.

Hebrew Bible: Solidifying Canon

Between 70 and 150 C.E., pivotal determinations regarding the Jewish Canon were solidified. As per the internal rabbinic tradition, the Council of Jabneh in 90 C.E. purportedly rendered definitive decisions regarding the Jewish Canon of Scripture.

While the historical accuracy of this council remains debatable, indications suggest that by the conclusion of the 2nd century C.E., a discernible trend towards heightened standardization of the Biblical Canon within Judaism was emerging.

Key Bible Versions with Timeline

But as the ages passed, so did the history of the Bible, adapted and translated to resonate with diverse cultures and languages. The following are a few key versions of the Christian Bible:

- 1The King James Version - commissioned in 1604, and completed in 1611.

- 2The Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition - a Catholic Bible published in 1966. It contains seven additional books which are not part of the standard Protestant Bible.

- 3The New International Version was first published in 1978.

- 4The New Revised Standard Version was released in 1989. It is widely used in Academia and within mainline Protestant denominations.

Summing up Conclusion: The History of the Bible

What is the Bible? At its core, the history of the Bible is a testament to the profound interplay of humanity's spiritual journey, cultural evolution, and intellectual exploration.

As we've journeyed through the development of the Hebrew Bible, we've unearthed the remarkable fusion of oral tradition and written record, scribal culture, and captivating manuscript tradition that gave rise to this enduring work of wisdom.

There's a unique opportunity to deepen your understanding of the foundational narratives that have shaped our world!

I invite you to embark on a journey of discovery with Dr. Bart Ehrman's enlightening course, "In the Beginning: History, Legend, and Myth in Genesis." Through six insightful lessons, you'll unravel the layers of Genesis, gaining insights into its historical context, legends, and enduring impact.

FREE COURSE!

WHY I AM NOT A CHRISTIAN

Raw, honest, and enlightening. Bart's story of why he deconverted from the Christian faith.

Over 6,000 enrolled!