History of Christianity: The First 300 Years (TIMELINE)

Written by Joshua Schachterle, Ph.D

Author | Professor | Scholar

Author | Professor | BE Contributor

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Verified! See our guidelines

Edited by Laura Robinson, Ph.D.

Date written: March 1st, 2024

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

In the first 300 years of the history of Christianity, a lot of pivotal events occurred. In that relatively short span of historical time, Christianity went from being a tiny Jewish sect to being the principal religion of the Roman Empire. How in the world did that happen?

In this article, I’ll focus on the most pivotal events, sticking as closely as possible to those we can verify historically, and trace the path this religion took from being a tiny band of outcasts to ruling the mightiest empire on Earth.

After a brief note on the founding of Christianity, I’ll look into what happened after Jesus’ death as his followers through the next three centuries developed their practices and beliefs and spread them from Judea into other areas of the Roman Empire. Here are some of the significant events.

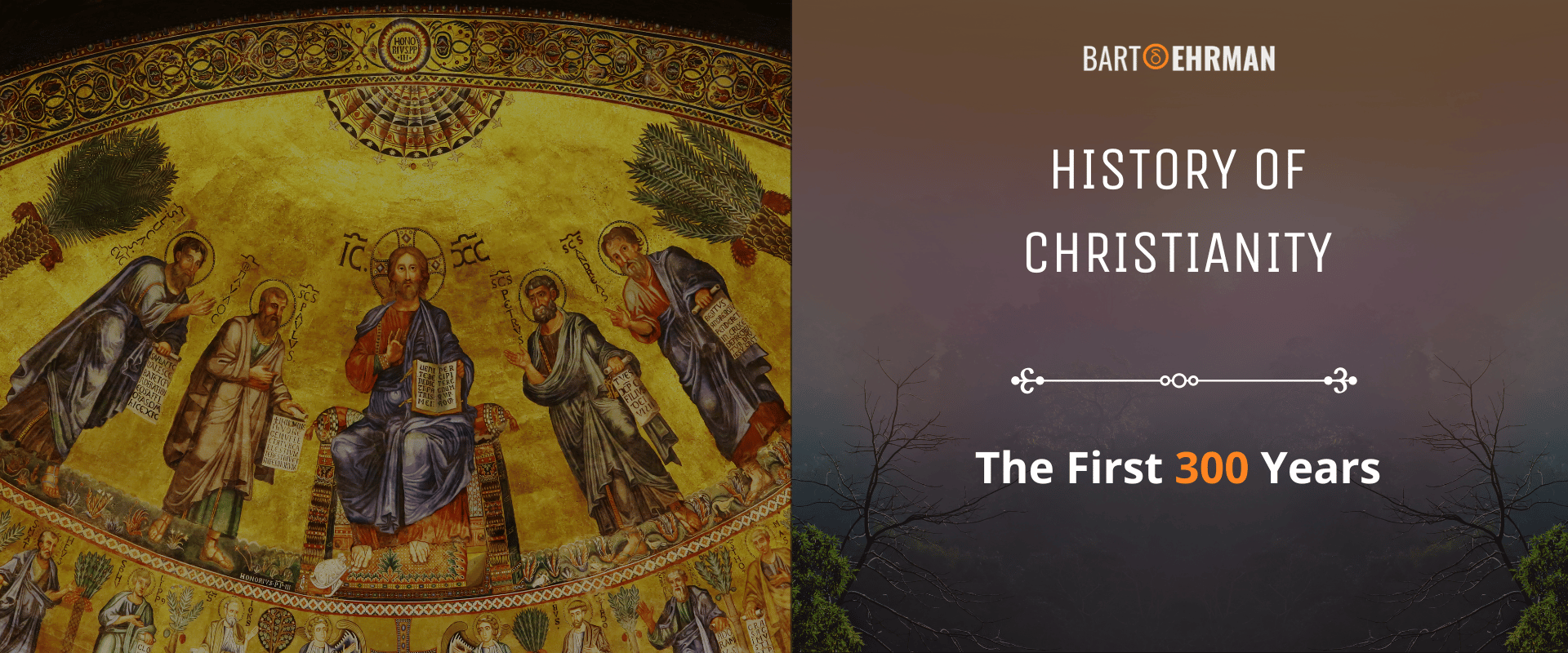

Date | Event |

|---|---|

4-6 BCE | Birth of Jesus of Nazareth |

26-30 CE | Ministry of John the Baptist |

30 CE | Crucifixion of Jesus |

30-35 CE | Earliest followers of Jesus establish their community in Jerusalem |

35-37 CE | Saul, otherwise known as Paul, converts to belief in Jesus as Messiah and becomes apostle to the Gentiles |

35-55 CE | Paul’s goes on missionary journeys to Corinth, Thessaloniki, Galatia, and many other Roman cities where he establishes Christian communities and writes letters to them |

48-50 CE | Council of Jerusalem where leaders of Jesus movement discuss the inclusion of and requirements for Gentiles |

58-60 CE | Paul imprisoned in Rome |

60-65 CE | Death of Paul |

60-68 CE | Death of Peter |

64 CE | Great Fire in Rome; Nero blames and executes Christians |

66-70 CE | First Jewish Revolt against Rome |

69-79 CE | Reign of Emperor Vespasian |

70 CE | Fall of Jerusalem under military supervision of Vespasian’s son Titus |

70 CE | Gospel of Mark written |

80-85 CE | Gospel of Matthew written |

85-95 | Gospel of Luke and the book of Acts written |

81-96 CE | Reign of the emperor Domitian, Vespasian's younger son. Domitian is the object of the anti-Roman hatred in the Book of Revelation. |

90-110 CE | Gospel of John written |

100-165 CE | Life of Justin Martyr, Christian apologist. Justin’s writings represent Christianity as a philosophy and the only valid heir to the Hebrew scriptures. |

112-113 CE | Pliny the Younger, Roman governor of Pontus-Bithynia writes to the emperor Trajan for advice about punishing Christians. Trajan says punishing people on unverified charges is not permitted. |

132-135 CE | Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (also known as the Bar Kochba Revolt). |

150-215 CE | Life of Clement of Alexandria, Christian teacher and theologian/philosopher. Clement's theology mixed Christian theology with Greek philosophical ideas. |

150-122 CE | Life of Tertullian, North African Christian apologist and heresy hunter. |

185-254 CE | Life of Origen of Alexandria, early Christian scholar and teacher. His writings, heavily influenced by Greek philosophy, would have a profound effect on Christian theology. |

249-251 CE | First major persecution of Christians under emperor Decius. |

257-260 CE | Persecution resumes under emperor Valerian |

260-340 CE | Life of Eusebius, Bishop of Caesarea, historian of early church. |

303 CE | Persecution begins under Diocletian |

312 CE | Battle of Milvian Bridge. Constantine adopts a symbol of Christ, the chi-rho, and defeats his Maxentius to become sole ruler of western empire. |

313 CE | Edict of Milan issued. It’s an agreement between Constantine, ruler of the West and Licinius, ruler of the East, giving full restitution of confiscated Christian property and allowing Christian worship in every part of the Roman empire. |

324 CE | Constantine defeats Licinius, becoming sole ruler of the Roman empire. |

325 CE | Constantine convenes the Council of Nicaea in an effort to settle theological differences among different church factions. |

337 CE | Death of Constantine |

This timeline of Christian history provides us with some broad talking points. I’ll use them to go into a bit more detail about some of the most important events which led to the spread of Christianity and its rise to prominence.

To do this, I’ll divide these 300 years into two eras: The Apostolic Age (30-100 CE) and the Ante-Nicene period (100-325 CE). If it seems like the time period allotted for the Apostolic Age is relatively short, remember that this period was particularly dynamic for the rise of Christianity from its humble beginnings.

The Founding of Christianity

We know that Jesus’ ministry was relatively short, probably no longer than three years. Although the Gospels say that Jesus spoke to enormous crowds, it’s impossible to know if this was true.

In the Gospel of Mark, for instance, Jesus often silences his disciples (and some demons) when they say he’s the Messiah. Scholars call this the “Messianic Secret”. Why would Mark do this? One explanation is that during Jesus’ lifetime, very few people thought he was the Messiah.

This Messianic Secret may have been a way for Mark to explain to non-Christian Jews why Jesus’ identity as the Messiah wasn’t better-known or accepted. Jesus had deliberately quashed his identity as Messiah until after his resurrection.

All of this merely points to the fact that the Jesus movement after his death was very small. According to the book of Acts, it included the twelve disciples (one replaced Judas Iscariot) and several members of Jesus’ family. Acts actually says there were 120 people in all, but even that number seems too large to fit into an upper room.

However, the spread of Christianity began in earnest when Paul was converted. Paul had an experience of the risen Christ and was convinced that he had been given a mission: to go take the good news of Jesus as salvific Messiah to the Gentiles. This he did with remarkable enthusiasm.

Had this mission to the Gentiles never happened, it seems likely that the Jesus movement would have remained a splinter sect of Judaism and, like the Sadducees or the Essenes, would eventually have died out.

Paul started and sustained communities of Gentile Christians in far-flung areas of the Roman Empire. This made it possible for the movement to continue to spread throughout the Empire for centuries. This also meant that even though Paul disagreed with Peter and the Jerusalem church on Jewish requirements for Gentiles, the movement stayed alive.

As Bart Ehrman says in Jesus Before the Gospels, each new convert likely told friends and neighbors about Jesus, who then told their friends and neighbors and eventually this led to the Empire-wide spread of Christianity.

So, having talked about the founding of this religion, let’s look at some of its key events in the Apostolic Age.

The Apostolic Age: The Spread of Christianity

In 64 CE, there was a huge fire in the city of Rome. According to our sources, the Roman emperor Nero blamed Christians for the fire. He thus initiated the first Christian persecution by an emperor. It’s likely that both Peter and Paul were executed in Rome as a result.

Around this same time, 66-70 CE, there was a major Jewish Revolt against the Romans . The end result was that not only was Jerusalem itself destroyed but the Temple was destroyed. Why was this so significant for Christianity?

First, as I mentioned, the first Christians still viewed themselves as Jews. In the book of Acts, we see them going to the Temple to worship as they always had. However, when the Temple was destroyed, this was in many ways, the end of the sacrificial side of Judaism. Without the Temple, were all the rituals and sacrifices necessary or even possible?

This started a major change in Christianity, which gradually, at least among Gentile converts, became less focused on the Judaism of its day. Of course, it also had a major impact on Judaism which gradually transferred its cultic focus to the text of the Hebrew Bible, resulting in rabbinic Judaism. In addition, according to tradition, the original Jerusalem Church had to flee Jerusalem for Syria. They continued to exist as Jewish Christians but were soon dwarfed by Pauline communities of Gentiles throughout the Roman Empire.

It was around this same time, 70 CE, that our earliest written Gospel, Mark, was written. It was at least partly based on oral traditions handed down over the four decades since Jesus’ death. However, it also contained much later reflections on Jesus’ significance as Messiah.

According to M. Eugene Boring, the author of Mark was not an eyewitness to the life of Jesus, nor did he get his information from eyewitnesses. Therefore, Mark’s principal sources were traditions that had been passed down for at least two generations, making their historical accuracy dubious at best.

Despite this, our next Gospels, Matthew and Luke, written between 80-95, would use Mark as a primary source, ensuring that later Christians would take Mark’s stories and sayings as “gospel truth.”

Scholars are in some disagreement about whether or not the author of the Gospel of John in 90-110 CE knew the other three Gospels. What is certain, however, is that John’s Gospel preserved an entirely different tradition in which the principal message of Jesus was not about the coming Kingdom of God, but rather about his own significance as the divine Logos or Word of God.

Finally, during the reign of the emperor Domitian from 81-96 CE, there were apparently more persecutions of Jews and Christians. This is why the author of the book of Revelation, known only as John, wrote his apocalyptic tirade against Domitian in 90-95 CE.

Ante-Nicene Period: Important Authors in the Rise of Christianity

Several key Christian authors lived and wrote in the 2nd century CE. Justin Martyr (100-165 CE) was a Gentile Christian apologist. The word “apologist” comes from the Greek word apologia which means a defense of one’s beliefs or behavior.

Many non-Christian Romans held disdain for Christianity, sometimes stemming from the perception that it was a lower-class religion for the uneducated. Justin, however, was not from the lower classes. He was born in a Greek city in Palestine but had little to no contact with the Judaism around him.

According to his Dialogue with Trypho, as a young man he began pursuing a philosophical education. This led him to various Greek philosophers, none of which satisfied his thirst for knowledge.

Finally, he met a Syrian Christian who convinced him of the superiority of Christianity to all the other philosophies he had studied. Historically, this dialogue, which purports to be with a Jewish man but is probably invented, tells us two important things about early 2nd-century Christianity: First, some, but not all, Gentiles had begun to differentiate between Christianity and Judaism as Justin did and second, students of Greek and Roman philosophy were becoming interested in Christianity.

In fact, another 2nd and 3rd-century author, Clement of Alexandria, would in some ways fuse the insights of Greek philosophy with Christian teachings. This led to Christian philosophical schools in Alexandria, Egypt, a great center of learning at the time.

One of Clement’s students, Origen of Alexandria, took the philosophical connection even further. His theological writings were heavily influenced by Platonic philosophy and would have an enormous impact on Eastern Christian teachings. Eventually, though, a mistrust of his philosophical bent grew in some circles and his writings were anathematized long after his death.

Another author, Tertullian (150-122), may have been the first Latin Christian author. Tertullian was extremely concerned with defining and maintaining orthodoxy among Christians. As such, he frequently harped on those he believed to be heretics. This is a bit ironic when we realize that at one point, he was drawn to a group that would later be considered heretical, the Montanists, although he doesn’t seem to have left the mainstream church.

Finally, jumping ahead to the 4th century, we have Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea and church historian. Eusebius wrote an exhaustive early church history from its beginnings in the 1st century to his own time during the reign of the Christian emperor Constantine. Scholars now know that much of his history was not completely historical, but it was nevertheless an important text.

Eusebius argued in his church history that all of history had been leading up to the advent and conquest of Christianity over the world. This was evident to him because his emperor, the first to declare himself a Christian, seemed like the culmination of a history of God’s salvation of the world. Needless to say, this conclusion was a bit premature.

Anti-Nicene Period: Persecutions

While there had been two official persecutions of Christians during the Apostolic Age, there were more to come during the Anti-Nicene period.

In 112 or 113 CE, Pliny, the governor of a province called Pontus-Bithynia (modern-day Turkey) wrote to the emperor Trajan for advice on what to do with Christians who had been arrested and brought to him. He noted that he had never been present at a trial of Christians – indicating that such trials had indeed already happened – and he was uncertain of three things:

First, should young Christians be treated differently from older ones? Second, should those who deny being Christians be pardoned? And finally, was being called Christians enough to condemn them to death or was it only certain crimes associated with being Christians?

Trajan gave four main responses. First, don’t pursue Christians for trial. Second, if the accused are found guilty of being Christian, then they must be punished (this usually meant execution). Third, if they deny being Christians and prove it by worshipping the Roman gods, they must be pardoned. Finally, anonymous accusations of Christians should not be taken seriously.

This gives us some important information about Roman policy toward Christians in the early 2nd century. There was no official persecution of them since Trajan said not to pursue them. However, if they came into custody, they would have to prove their loyalty to Rome by worshipping the gods (on behalf of the welfare of the empire) or be executed.

The next official persecution of Christians didn’t occur until the reign of Decius from 249-251 CE. He issued an edict which said that everyone in the Roman Empire, with the exception of Jews, must sacrifice to the gods and the welfare of the Emperor in the presence of a Roman magistrate, and get a written certificate to prove it had been done. Jews were exempt as a matter of policy, because they had their own sacrifices and had agreed to sacrifice to their god on behalf of the emperor.

It's impossible to know how many Christians sacrificed to the gods to save their lives vs. how many refused and were executed. Many Christians also went into hiding to avoid the conflict altogether.

After the edict had lapsed at the death of Decius, many who had renounced Christianity for their own safety wanted to return and there were major debates over whether this should be allowed.

Between 257-260 CE persecutions resumed under the emperor Valerian. In 257 CE, Christian clergy were ordered to make sacrifices to the Roman gods or face exile. The following year, Valerian ordered that all Christian leaders be executed. Other Christians had their property confiscated and some were reduced to slaves. This persecution ended with Valerian’s death in 260 CE.

The most severe persecution of Christians was yet to come, however, from the emperor Diocletian. In 303, he ordered that the newly built Christian church at Nicomedia be destroyed, its Scriptures burned, and its treasures seized. Later that same year, he ordered that all priests and bishops be imprisoned. Eusebius writes that so many were arrested that they had to release the criminals to fit them all in (this may be hyperbole).

The final, brutal act of Diocletian in 304 was to order that all men, women, and children had to assemble and make a collective sacrifice to the Roman gods. If they refused, they were executed.

Ante-Nicene Period: Constantine and the Triumph of Christianity

The emperor Constantine is one of the most important figures in the history of Christianity. He was the first Christian emperor and his reign signified a pivotal turning point in the religious landscape of the ancient world.

Constantine was born on February 27 in a city called Naissus (modern-day Niš, Serbia). While early sources fail to tell us the year of his birth, his early biographer, the aforementioned Eusebius, gives us some clues that lead historians to believe he was born sometime between 271-277 CE.

His father was Flavius Constantius, a nobleman and decorated soldier. During the reign of the emperor Diocletian, the empire was split and Constantius became a co-emperor, ruling over one part of the Western Roman Empire.

Constantine’s mother was named Helena. As Hans Pohlsander notes, she was probably not the legal wife of Constantius but rather a concubine. Unlike Constantius, she came from very humble beginnings.

Like his father, Constantine became a Roman soldier, fighting to defend and expand the Roman Empire. He fought therefore against the Persians and some of the Germanic tribes in the Danube region. For many noble-born men, a successful military career was a step on the path to becoming emperor, a way of proving oneself as a conqueror and defender of the empire.

As Constantius was dying, he gave his approval for Constantine to succeed him as one of the co-emperors. Most of the areas under Constantius’ rule, as well as all the soldiers under Constantine’s command, accepted Constantine as their ruler. Constantine thus wrote to his co-emperor Galerius asking to be legitimized as an emperor. Galerius, realizing that to say no to such a popular figure might cause a civil war, reluctantly agreed.

Constantine was in charge of Britain, Spain, and Gaul (modern-day France). However, another co-emperor, Maxentius, wanted control over the regions Constantine controlled. Thus began a civil war.

This all came to a head at the final battle at the Milvian Bridge in northern Rome. In this battle, Constantine defeated Maxentius, thus leading eventually to his becoming sole emperor of Rome. However, this battle was significant to Christianity for another reason: it was at this battle that he became a Christian.

The conversion of Constantine to Christianity is arguably the most pivotal aspect of his legacy.

Our earliest source about Constantine’s conversion is Lactantius, an early Christian author who would become Constantine’s advisor. According to Lactantius, the night before the battle at the Milvian Bridge,

Constantine was directed in a dream to cause the heavenly sign to be delineated on the shields of his soldiers, and so to proceed to battle. He did as he had been commanded, and he marked on their shields the letter Χ, with a perpendicular line drawn through it and turned round thus at the top, being the cipher of Christ. Having this sign, his troops stood to arms.

This symbol consisted of the Greek letters X (pronounced “Key”) and Ρ (pronounced “Row”), the first two letters in the Greek spelling of “Christ.” With this symbol emblazoned on their shields, Constantine’s forces won the battle. Constantine, as a result, became a Christian. This symbol would continue to represent Christians for centuries.

After meeting with his co-emperor Licinius in 313 CE, Constantine issued the Edict of Milan which said that all persecution of Christians must end, that all property confiscated from them during the persecution must be returned, and that all people in the Roman Empire were free to practice whatever religion they wanted.

For Constantine, all religions were to be tolerated, none persecuted. However, ending the persecution and even ending the possibility of further persecution during his reign was a huge gesture which certainly contributed to the growth of Christianity.

While Constantine’s conversion to Christianity may have been sincere, he was still a political leader. He wanted unity in his empire.

With Christianity now legal throughout the Roman Empire, there was a dizzying diversity of Christian beliefs and practices. In addition, there was no central Church structure so there was no way of definitively adjudicating theological arguments or even marking important Christian calendar events.

One of the more prominent unsettled theological arguments started in Alexandria, Egypt. A priest named Arius claimed that Jesus, since he had been created by God the Father, was subordinate to God rather than equal to him. While many agreed with this position, Alexander, the bishop of Alexandria, did not, claiming that Jesus was coeternal with God. He held smaller meetings of clergy in Alexandria to discuss the matter but nothing was ultimately resolved.

Constantine heard about this controversy and decided that this and other divisive issues needed to be resolved once and for all. Accordingly, he convened a synod or council of bishops in the city of Nicaea in modern-day Turkey in 325 CE. The bishops came from all over the Roman Empire, although due to the difficulty of travel in the ancient world, most came from the eastern regions nearer to Nicaea.

In his zeal to bring the church to unity, Constantine’s agenda at the council included the following issues: the Arian debate I mentioned above, controversy over the dating of Easter, and disputes over a schism called the Melitians (a group of Christians who believed that those who had renounced their faith under persecution shouldn’t be allowed to return).

Constantine didn’t really care which way the debates went, only that they were resolved and made official. In short, the council decided that Arius was wrong, as outlined by the subsequent Nicene Creed. It also decided on the dating of Easter and that the Melitians were wrong.

People on the losing sides of these issues didn’t just disappear overnight. But the positions taken at the council became the winning side under Constantine’s rule and many of those positions are still a part of Christianity today.

Conclusion

Could the original twelve disciples ever have imagined Christianity’s triumph over Rome? The answer is almost certainly no. And yet, within 300 years of Jesus’ death, that is exactly what happened.

During the Apostolic Age, we saw the spread of Christianity to far-flung areas of the empire. In fact, while there certainly were theological developments during this age, it seems that the main concern of Christians was getting their gospel to as many people in as many places as possible.

This age saw the execution of Peter, Paul, and other prominent early Christians, but also the composition of the four canonical Gospels, texts that would only further the spread of Christianity.

During the Ante-Nicene period, great scholars and theologians such as Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, and Origen produced complex theological texts that would further develop Christian theological ideas.

More and more severe persecutions followed sporadically under certain emperors until Constantine, the first Christian emperor, brought the rise of Christianity to its pinnacle. For this reason, church historian Eusebius wrote that Constantine was a kind of savior himself, chosen by God to end the persecutions and make the Roman Empire into a Christian power.