Catholic vs Christian: What Are the Key Differences?

Written by Marko Marina, Ph.D.

Author | Historian | BE Contributor

Verified! See our guidelines

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Date written: March 1st, 2024

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

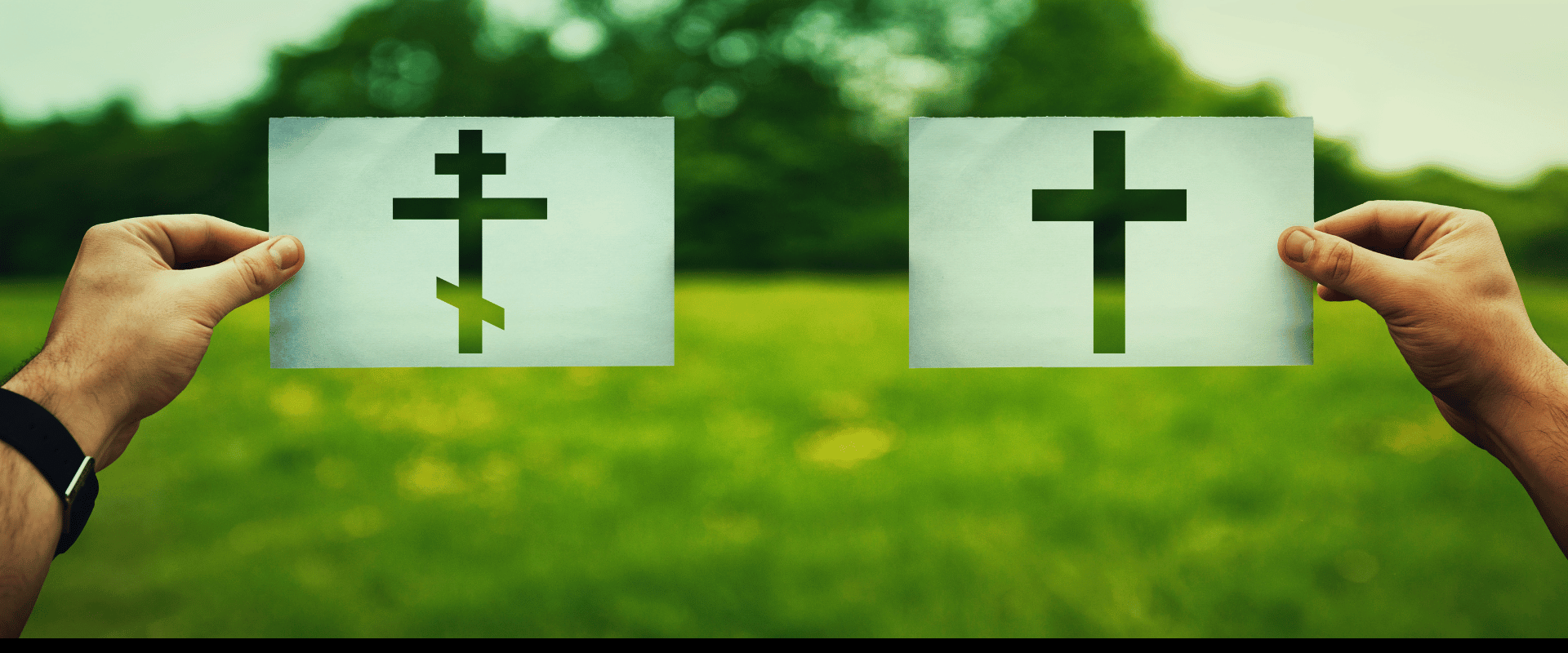

For centuries, Christianity has been a mixed bag of diverse theological beliefs, practices, and traditions. Among the most significant divides is that between Catholics and Protestant Christians, a schism that dates back to the Reformation in the 16th century.

This “Catholic vs Christian” division, rooted in deep theological disagreements, has shaped the religious landscape of the world in profound ways. Yet, despite these differences, both traditions share the same foundational faith in Jesus Christ, prompting an exploration of what unites and divides them.

This historical backdrop raises several intriguing questions:

These questions, among others, pave the way for a deeper understanding of the diverse world of Christian belief and tradition.

By exploring the key differences in beliefs, practices, and theological underpinnings that distinguish Catholics from their Christian (Protestant) counterparts, we endeavor to provide our readers with a clear and accessible understanding of this complex subject matter.

Moreover, through an objective examination of "Catholic vs. Christian beliefs", we aspire to bridge gaps in understanding and appreciation for the rich tapestry that makes up Christianity in its many expressions.

Catholic vs. Christian Discourse: A Methodological Approach

In the realm of religious studies, scholars generally regard Catholicism as an integral branch of the Christian tradition. Yet, there exists a subset of conservative thinkers, such as James White, who challenge this classification, arguing that Catholics shouldn’t be considered Christians.

This perspective isn’t isolated to individuals but extends to certain conservative Protestant denominations, which either outright reject Catholicism's Christian status or express confusion over the distinctions between Catholics and what they refer to as Christians.

The heart of this debate, encapsulated in the "Catholic vs. Christian" discourse, lies not in questioning the Christian faith of Catholics but in understanding the doctrinal divergences that separate Protestant beliefs from Catholic practices.

This article aims to unpack these differences. By exploring the theological, liturgical, and ecclesiastical distinctions between Protestant and Catholic adherents, we endeavor to shed light on the complexities that underpin this discourse, paving the way for a more informed and respectful dialogue within the broader Christian community.

In adhering to what Bart D. Ehrman describes as "methodological agnosticism," we commit to a discourse that is informed by an academic and neutral standpoint, avoiding any bias towards a particular set of religious beliefs.

This approach allows us to engage with the "Catholic vs. Christian" discussion in a manner that is respectful, informative, and inclusive of the diverse beliefs that constitute the Christian faith.

Recognizing the complexity of the distinctions between Catholic and Christian beliefs, we’ll first present a concise table outlining the key differences. This will serve as a foundation for our deeper exploration into these diverse theological perspectives, ensuring a clear and structured understanding as we navigate through the intricacies of this discussion.

Catholic vs. Christian: Summarizing the Key Differences (TABLE)

The following table encapsulates the fundamental differences, providing a clear overview of contrasting beliefs, practices, and perspectives.

Aspect | Catholic Belief | Christian (Protestant) Belief |

|---|---|---|

The Role of Scripture | Sacred tradition, Scripture, and the Church's teaching authority are inextricably linked. | Scripture alone is the supreme authority, independent of the Church's tradition and hierarchy. |

Biblical Canon | Includes the Apocrypha in the Old Testament. | Excludes the Apocrypha, adhering only to the OT books originally written in Hebrew. |

Salvation | Salvation is a synergy between God's grace and good works. | Salvation is by faith alone, without contribution from human actions. |

Authority of the Pope | The pope (bishop of Rome) is the supreme ecclesiastical authority. | Rejects the supreme authority of the pope, with some denominations viewing the papacy extremely critically. |

Veneration of Mary and Saints | Holds Mary and the saints in high esteem, with doctrines supporting the Immaculate Conception, Divine Motherhood, Perpetual Virginity, and Assumption of Mary. | Generally rejects the veneration of Mary and the saints. |

Sacraments | Recognize seven sacraments as a means of God’s grace. | Accepts only Baptism and the Eucharist as sacraments instituted by Jesus. |

Jesus’ Brothers | Interprets references to Jesus’ brothers as cousins thus supporting the doctrine of the Perpetual Virginity of Mary. | Views all references to Jesus’ brothers in the NT as evidence for biological siblings. |

Having outlined the foundational distinctions through our comparative table, let's now delve deeper into these theological landscapes, beginning with a closer look at Catholicism—its origins, beliefs, and practices that have shaped the history of Western Civilization in many ways.

What is Catholic? A Brief Overview of Catholicism

Within the broad spectrum of Christianity, Catholicism manifests in several distinct traditions. However, for this article, we’ll focus on the most common and globally recognized form: Roman Catholicism.

The term "Catholic" itself originates from the Greek word "katholikos," meaning "universal" or "pertaining to the whole." This etymology underscores the Catholic Church's claim of universality, a central tenet that has guided its mission and theological outlook.

What is Catholic? Roman Catholicism is grounded in a rich well of beliefs and practices that have been developed and refined over millennia. At the heart of Catholic doctrine is the importance of Tradition—with a capital "T."

This concept, as articulated by Lawrence S. Cunningham, emphasizes that Catholicism values Tradition as a "handing down" process. This isn’t merely a passive transmission of beliefs but a dynamic act of preservation and preaching.

Catholics hold that the Gospel and the worship of the Church have been continuously handed down from the era of Jesus Christ to the present day, making the Church a living witness to the faith.

This sacred Tradition is entrusted primarily to the bishops, who are viewed as the legitimate successors of the Apostles, ensuring the apostolic lineage and the integrity of the faith.

Central to Roman Catholic belief is the sacramental system, with the Eucharist—or Holy Communion—at its core. This sacrament, considered the true body and blood of Jesus Christ (doctrine of transubstantion), epitomizes the profound mystery and grace of Catholic worship.

Additionally, Catholics underscore the significance of the Virgin Mary and the saints, viewing them as exemplars of faith and intercessors between the faithful and God. Furthermore, Catholic beliefs include the doctrine of perpetual virginity of Mary which holds that Jesus’ mother was a virgin before, during, and after Jesus’ birth.

The Catholic Church also upholds the pivotal authority of the Pope, the Bishop of Rome, as the spiritual leader and successor to Saint Peter, affirming a hierarchical structure that has guided the faithful through centuries of change and challenge.

In addition to its foundational beliefs and practices, Roman Catholicism offers a distinctive perspective on the path to salvation, intertwining the roles of grace and good works. Central to Catholic theology is the belief that salvation is a process initiated by God's grace, which is freely given and not earned by human merit.

However, unlike some Christian (Protestant) traditions, Catholics hold that faith must be lived out through good works as a response to God's grace. Good works, including charity, moral living, and participation in the sacraments, are seen as both evidence of faith and a means through which God dispenses grace to aid believers in their spiritual journey.

Having outlined the fundamental beliefs and practices of Roman Catholicism, particularly its distinctive stance on salvation that intertwines grace with good works, we transition to exploring the roots of the Christian (Protestant) tradition.

This pivot allows us to delve deeper into the "Catholic vs. Christian" discussion which will ultimately help us understand the difference between Catholic and Christian (Protestant).

What is Christianity? A Brief Look at the Origin of Protestantism

The Protestant Reformation, a pivotal epoch in the history of Christianity, was significantly shaped by the contributions of Martin Luther and John Calvin, among others.

Their roles in the Reformation not only catalyzed a theological revolution but also laid the groundwork for the enduring "Catholic vs. Christian" dialogue that distinguishes between Catholicism and Protestant denominations.

Martin Luther, a German monk and theologian, ignited the Reformation in the early 16th century with his critique of certain practices and doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church, most famously through his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517.

Luther's call for reform was rooted in the belief that salvation is obtained through faith alone, a stark contrast to the Catholic view that emphasizes the synergy of faith and good works.

His translation of the Bible into the vernacular made the scriptures more accessible, encouraging personal interpretation and challenging the Church's role as the sole interpreter of Christian doctrine.

John Calvin, a French theologian and pastor, furthered the Reformation's impact in the mid-16th century, particularly with his teachings and writings in Geneva. Calvin is best known for his doctrine of predestination and his emphasis on the sovereignty of God in salvation, as well as for his contributions to the organization and governance of the Protestant Church.

His work, "Institutes of the Christian Religion," remains a foundational text for Reformed theology and has profoundly influenced Protestant thought and practice.

Together, Luther and Calvin's legacies represent crucial junctures in the development of Protestant Christianity. Their advocacy for scriptural authority over church tradition and a personal, direct relationship with God without the mediation of the church hierarchy were fundamental to the formation of various Protestant denominations.

While this section doesn’t delve deeply into the theological nuances of Luther and Calvin's beliefs, their roles are essential to understanding the historical backdrop against which the "Catholic vs. Christian" distinctions emerged, setting the stage for a more detailed exploration of the differences between Catholic and Christian.

Delineating the Differences Between Catholic and Christian

As we pivot to a detailed examination of the distinctions within the Christian faith, it becomes imperative to explore the nuances that define the "Catholicism vs. Christianity" polemic. This segment sets the stage for a deeper dive into the theological, liturgical, and doctrinal differences between Catholic vs. Christian beliefs, practices, and perspectives.

The Role of Scripture in Catholicism and Christianity

In the discourse on "Catholic vs. Christian" beliefs, the role and authority of Scripture emerge as pivotal points of divergence. For Protestant Christians, Scripture alone is seen as the supreme authority, independent of and surpassing the authority of popes and church councils.

This principle of Sola Scriptura underscores a fundamental difference between Catholic and Christian (Protestant) approaches to Biblical authority.

In contrast, Catholic doctrine holds that Scripture must be interpreted within the context of the Church's tradition and hierarchy. According to the "Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation," sacred tradition, sacred Scripture, and the teaching authority of the Church are inextricably linked, with none able to stand without the others.

Catholic vs. Christian Bible

The difference between the Catholic and Christian (Protestant) Bible further illustrates the "Catholic vs. Christian" theological divide.

The Catholic Bible includes seven books in the Old Testament known in Protestant circles as the Apocrypha, such as 1 and 2 Maccabees, which are not found in the Protestant Bible. The Catholics usually designate them as Deuterocanonical books. They are:

This distinction between the Catholic and Christian (Protestant) Bible originated from the Reformation in the 16th and 17th centuries, though its roots trace back to the earliest days of Christianity.

Early Christians, primarily Greek-speaking, utilized the Septuagint—a Greek collection of Jewish Scriptures that included both books originally written in Hebrew and those written in Greek, like 1 and 2 Maccabees. This version of the Scriptures was widely used among Greek-speaking Jews and early Christians alike, without an official canon.

However, by the 2nd century CE, as Jews officially canonized their Scriptures to include only those books originally written in Hebrew, the Christian Old Testament continued to embrace the Greek books of the Septuagint. This inclusion reflects the early Christian community's broader understanding of sacred texts.

During the Reformation, figures like Luther and Calvin advocated for a return to the Hebrew originals, excluding the Greek texts from the Protestant Old Testament. This decision underscored a significant "Difference between Catholic and Christian" scriptural canons, with the "Catholic Bible vs. Christian Bible" distinction highlighting the varying approaches to what constitutes authoritative sacred scripture.

The Issue of Salvation for Catholics and Christians

At the core of Christian (Protestant) theology lies the principle of justification by faith alone, a concept that defines their understanding of how individuals are saved. This doctrine posits that salvation is granted solely through faith in Jesus of Nazareth as the Savior, without any contribution from human actions toward their redemption.

Embracing the Apostle Paul's declaration that “The righteous will live by faith (Rom 1:17)”, Protestant Christians maintain that salvation is a gift passively received from God. It’s through trust in Christ's atoning sacrifice alone that sinners are deemed justified before God.

This stance presents a stark contrast to the Catholic view, which, as we’ve seen, articulates salvation as a synergy between the grace of God and good works performed by the believer.

The "Catholic vs. Christian beliefs" dialogue thus encompasses a fundamental divergence in understanding salvation's mechanics. In other words, the difference between Catholic and Christian perspectives on salvation highlights a pivotal theological divide.

This distinction not only underscores the diverse interpretations within Christianity but also reflects the rich tapestry of thought that has historically shaped the faith's evolution.

Catholicism vs. Christianity: The Authority of the Pope

In the landscape of "Catholic vs. Christian" theological distinctions, the authority of the pope serves as another significant point of divergence. Rooted in the principle of Sola Scriptura, Christians fundamentally reject the papal office as the supreme ecclesiastical authority.

This stance stems from a broader rejection of any religious authority that supersedes or rivals the authority of the Bible. Consequently, Protestants don’t recognize the pope as the successor of St. Peter in the sense that Catholic doctrine asserts.

Scholarly Insights

Did Martin Luther really nail his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg? Traditionally hailed as the spark of the Protestant Reformation on October 31, 1517, the vivid image of Luther's defiant act symbolizes the challenge against the corruption of the Catholic Church.

Yet, contemporary accounts don’t directly document the event, and evidence mainly emerges from later narratives, including those from Luther's associate, Philipp Melanchthon, years after Luther’s death. This enduring enigma still haunts scholars, perpetuating debates over the truth behind what has become one of the most iconic moments in religious history.

Within some of the more conservative Protestant communities, this rejection is taken further, with the pope at times controversially described as the Antichrist. This characterization, though not universally held among Protestants, reflects the depth of theological and ecclesiastical rifts that have historically divided Protestant and Catholic perspectives.

Conversely, the Catholic Church holds the pope as the Vicar of Christ on Earth, asserting his role as the spiritual successor to St. Peter, whom they regard as the first bishop of Rome and the rock upon which Jesus built his church.

Throughout the Middle Ages, in a religious sense, dominated by the Catholic Church, the pope ("Christ's vicar") oversaw Christendom as a whole. Bishops, seen as successors of Jesus' apostles, were responsible for their dioceses, and parish priests served the laity directly in their parishes. This was (and still is) the institutional backbone that holds the Catholic Church together.

Moreover, the dogma of papal infallibility, proclaimed in the First Vatican Council of 1870, articulates that the pope is preserved from the possibility of error when he declares a doctrine concerning faith or morals to be held by the whole Church.

This dogma, often misunderstood, doesn’t imply that the pope is incapable of sin or error in his judgments. As Karl Keating explains: “Papal infallibility extends only to matters of faith or morals—not to Church customs, not to sports, not to literature, not to most things of everyday life. And infallibility comes into play only when the pope ‘proclaims by a definitive act’. This means a formal, public statement. An offhand comment over lunch doesn’t count.”

The concept of papal infallibility and the supreme authority of the pope underscores another fundamental difference between the Catholic and Christian perspectives on God, religion, salvation, and sin.

Catholic vs. Christian Beliefs: The Virgin Mary

In the discourse on "Catholic vs. Christian" differences, the role and veneration of saints, particularly the Virgin Mary, provide another strong demarcation between (Protestant) Christian and Catholic practices.

Christians, adhering strictly to the principle of justification by faith alone, reject any religious practices they perceive as not grounded in this doctrine. This includes prayers to saints, participation in pilgrimages, and practices of radical asceticism.

They argue that such practices detract from the sole efficacy of faith in Christ for salvation and, in some cases, attribute to them the character of works-righteousness, which they believe contradicts the core message of the Gospel.

The contrast becomes even more pronounced in the context of Marian veneration. The Catholic Church holds the Virgin Mary in high esteem, articulated through the four Marian Dogmas:

Protestant Christians, however, generally reject these dogmas, aligning with their broader theological stance that emphasizes a direct relationship with God through Christ, without the intercession of saints or veneration of Mary beyond recognizing her as a blessed and highly favored servant of God.

While they acknowledge Mary's importance as the mother of Jesus, they don’t accord her the same level of doctrinal or devotional emphasis as seen in Catholicism. Through this lens, the "Catholic vs. Christian" debate reveals deep-rooted theological and ecclesiological distinctions that have shaped the identities and practices of these traditions.

Catholic vs. Christian: The Role and Number of Sacraments

In the ongoing exploration of the differences between Catholics and Christians, the sacraments also represent an area of divergence. Protestant Christians, guided by the principle of Sola Scriptura, accept only those sacraments that they believe are instituted by Christ and clearly rooted in Scripture.

This criterion leads most Christian (Protestant) denominations to recognize two sacraments: Baptism and the Eucharist (or Lord's Supper). These rites are viewed as direct commands from Jesus to His followers, found explicitly in the New Testament, and are thus embraced as essential elements of Christian faith and practice.

In stark contrast, the Catholic Church upholds seven sacraments:

Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Penance (Confession), Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders, and Matrimony.

As the Catechism of the Catholic Church explains, sacraments are seen as the “efficacious signs of grace, instituted by Christ and entrusted to the Church, by which divine life is dispensed to us.”

The Catholic perspective sees these sacraments not merely as symbolic acts but as effective signs of grace, by which God dispenses His blessings directly to the faithful.

This comprehensive sacramental system reflects a deep sacramental theology in Catholicism, where the sacraments are seen as integral to spiritual life and growth, marking key stages and aspects of the Christian journey.

As we approach the conclusion of our exploration, we now turn to our final example, further illuminating the differences between Catholics and Christians.

Catholic vs. Christian Beliefs: Jesus’ Brothers?

Catholics, drawing on the interpretation championed by Jerome, a prominent early Church father, posit that references in the New Testament to Jesus’ brothers are to be understood as cousins or close relatives - not biological siblings.

This interpretation is rooted in the broader context of the Church’s tradition, which holds to the already-mentioned dogma of the Perpetual Virginity of Mary. It’s an emblematic illustration of the Catholic approach to Scripture and tradition, where the latter plays a crucial role in interpreting the former.

Contrastingly, the dominant view among (Protestant) Christians is that the references to Jesus' brothers in the New Testament (such as James, Joses, Judas, and Simon) are to be taken literally, suggesting that Jesus had biological siblings.

This interpretation aligns with a straightforward reading of Scripture, emphasizing the text's plain meaning without the lens of later theological developments. It’s noteworthy to mention that some Catholic scholars such as John P. Meier also accept that Jesus had real brothers.

Protestant scholars like Ben Witherington III note that the issue of Jesus' brothers became more pronounced as the early church, moving away from its Jewish roots, embraced ascetic ideals and became predominantly Gentile. This shift underscored a departure from Jewish customs, which celebrated fertility and the bearing of children, thus challenging the notion of perpetual virginity.

The differing views on Jesus' brothers between Catholics and Christians not only highlight theological and hermeneutical differences but also reflect broader themes in "Catholic vs. Christian" relations, such as the role of tradition in scriptural interpretation and the influence of cultural context on theological developments.

While I, as a historian, find the Christian (Protestant) position more compelling, recognizing it as closely aligned with a direct interpretation of the Biblical texts, this discussion exemplifies again the rich tapestry of differences between Catholics and Christians.

Summing up Conclusions

In conclusion, our journey through the nuances of "Catholic vs. Christian" beliefs, practices, and theological underpinnings reveals a mosaic of faith shaped by history, scripture, and doctrine.

From the pivotal roles of figures like Luther and Calvin in challenging and reforming religious thought, to the deep-seated traditions and teachings of the Catholic Church, we've traversed a landscape marked by divergence yet bound by a common pursuit of divine truth.

As we close this chapter, let us carry forward the spirit of objective analysis, fostering a dialogue that respects differences, seeks understanding, and appreciates the rich tapestry that Christianity, in all its expressions, offers to the world.

Following our exploration of the differences between Catholics and Christians, we invite our readers to delve deeper into the roots of Biblical interpretation with the captivating course “In the Beginning: History, Legend, and Myth in Genesis”.

Led by renowned scholar Bart D. Ehrman, this course offers an unparalleled journey into the Book of Genesis, viewed through the lens of history, legend, and myth. Ehrman's scholarly approach demystifies the complexities of Genesis, providing insights into its historical context and enduring significance.