Bible in Chronological Order (Every Book Ordered by Date Written)

Written by Marko Marina, Ph.D.

Author | Historian | BE Contributor

Verified! See our guidelines

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Date written: July 6th, 2024

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

Many assume the Bible follows a straightforward chronological order. They open its pages expecting a seamless narrative from Genesis to Revelation, yet this assumption often leads to misconceptions.

The same goes for the Gospels, when people believe that Matthew was written before Mark, or that the Gospels preceded Paul’s epistles. Understanding the true order of the Bible, however, requires a deeper dive into historical scholarship and textual analysis.

The reality is that the Bible, both in the Old and New Testaments, is a compilation of different texts written over centuries. Each book has its historical context, audience, and purpose. For instance, while many place Matthew before Mark due to its position in the New Testament, most scholars agree that Mark was the first Gospel written.

Exploring the Bible in chronological order unveils a fascinating journey through Israelite and early Christian history. This article aims to provide a scholarly overview of the approximate composition dates for Old and New Testament books, thus acknowledging the complexities and debates that often surround them.

While a detailed examination of each book's dating is beyond the scope of this piece, we’ll highlight some notable examples and direct you to further resources for in-depth study.

Understanding the true order of the Bible not only enriches our appreciation of these ancient texts but also illuminates the historical backdrop against which they were written. Join us as we piece together the timeline of the most important collection of text in the history of the Western world.

Old Testament Books in Order

For many of the books in the Old Testament, pinpointing the exact year or even century of composition is challenging due to a lack of internal evidence and external attestations. Nevertheless, what follows is a hypothetical list based on contemporary scholarship.

Book | Approximate Dating |

|---|---|

The Book of Hosea | 8th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Amos | 8th-7th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Isaiah | From the 8th (earliest strata) to the 6th-century B.C.E. (final composition) |

The Book of Zephaniah | 7th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Nahum | End of the 7th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Joel | End of the 7th or the beginning of the 6th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Joshua | Late 7th or early 6th century B.C.E. |

1 and 2 Kings | Late 7th or mid-6th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Psalms | Possibly from the 10th to the 5th century B.C.E. (highly speculative) |

The Book of Genesis | 7th-5th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Exodus | 7th-5th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Leviticus | 7th-5th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Numbers | 7th-5th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Deuteronomy | 7th-5th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Jeremiah | 7th-4th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Habakkuk | End of the 7th or the beginning of the 6th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Judges | 6th century B.C.E. |

1 and 2 Samuel | 6th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Haggai | 6th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Lamentations | 6th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Obadiah | 6th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Ezekiel | 6th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Ruth | 6th-5th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Zechariah | 6th-5th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Job | 6th-4th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Micah | Early 5th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Malachi | Early 5th century B.C.E. |

1 and 2 Chronicles | 5th century B.C.E. |

Book of Ezra | 5th century B.C.E. |

The Book of Ecclesiastes | 5th-4th centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Jonah | 5th-4th centuries B.C.E. |

Song of Songs | 5th-3rd centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Nehemiah | 4th-3rd centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Esther | 4th-3rd centuries B.C.E. |

The Book of Daniel | 2nd century B.C.E. |

The Book of Proverbs | Impossible to pinpoint |

It’s important to emphasize again that these dates are hypothetical and based on standard commentaries and scholarly studies of the Old Testament available for purchase on Amazon (e.g. M. Coogan’s The Old Testament: A Historical and Literary Introduction and The Oxford Bible Commentary edited by John Barton and John Muddiman). (Affiliate Disclaimer: We may earn commissions on products you purchase through this page at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our site!)

While this information reflects the opinion of many scholars, there is considerable debate, and not all historians agree with these dates. The complexities and nuances of biblical scholarship mean that our understanding of these texts continues to evolve. Let’s now turn to the New Testament, approaching the Bible in chronological order.

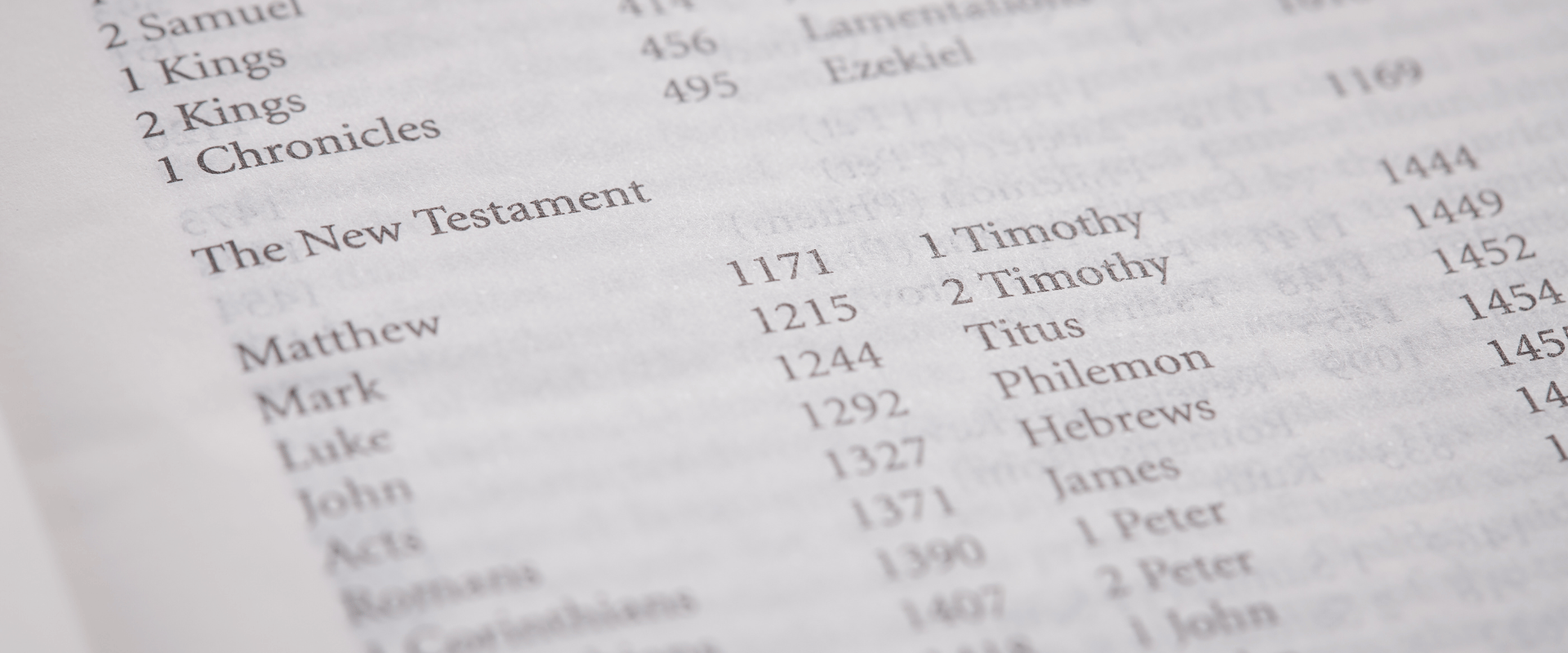

New Testament Books in Order

When moving into the area of the New Testament, we find ourselves on much more certain ground concerning the texts’ dating. Although the exact dates are difficult to determine, scholars can attribute dates for most New Testament books to within around a decade.

This relative certainty stems from the fact that, in contrast to most Old Testament books, there is just enough internal and external evidence.

The following table relies on the widely accepted scholarly view that the deutero-Pauline epistles (2 Thessalonians, Ephesians, Colossians, Hebrews, 1 and 2 Timothy, and Titus) were likely written by later authors who attributed their works to Paul.

Date | Approximated Dating |

|---|---|

1 Thessalonians | C. 49 C.E. |

Galatians | C. 49-51 C.E. |

1 Corinthians | C. 54-55 C.E. |

2 Corinthians | C. 55-56 C.E. |

Romans | C. 56-57 C.E. |

Philemon | 55 C.E. or 61-63 C.E. |

Philippians | C. 59-62 C.E. |

The Gospel of Mark | C. 70 C.E. |

2 Thessalonians | 70-90 C.E. |

1 Peter | 70-110 C.E. |

The Gospel of Matthew | 80-90 C.E. |

The Gospel of Luke | 80-90 C.E. |

The Acts of the Apostles | 80-90 C.E. |

Colossians | 80-100 C.E. |

Ephesians | 80-100 C.E. |

The Epistle to the Hebrews | 80-100 C.E. |

The Epistle to James | 80-100 C.E. |

The Gospel of John | 90-100 C.E. |

The Epistle of Jude | 90-100 C.E. |

The Book of Revelation | C. 96 C.E. |

1, 2, and 3 John | C. 100 C.E. |

1 and 2 Timothy | 90-120 C.E. |

Titus | 90-120 C.E. |

2 Peter | 110-140 C.E. |

It’s essential to reiterate that these dates are approximate and based on the best available evidence and scholarly consensus.

Some scholars disagree about particular books. Maurice Casey, for instance, argued in Aramaic Sources for Mark’s Gospel that Mark was written as early as the 40s C.E., and Richard Pervo claimed that Luke and Acts were written in the first part of the 2nd century.

However, I follow the dating still commonly used in well-acclaimed studies such as Bart D. Ehrman’s The New Testament: A Historical Introduction and Raymond E. Brown’s The Introduction to the New Testament. Furthermore, mainstream French scholarship also accepts these dates, as evidenced by Daniel Marguerat’s book Introduction au nouveau testament.

Having presented the books of the Bible in chronological order, we now turn our attention to some notable examples to present the basic arguments for their standard dating. As mentioned earlier, a comprehensive review of each book is beyond the scope of this article.

Instead, we’ll focus on a few significant examples from both the Old and New Testaments. Stay with us as we delve into the intriguing world of biblical studies and uncover the historical context behind these ancient texts.

Dating the Old Testament Books in Order: Some Notable Examples

The Pentateuch

The Torah, also known as the Five Books of Moses, constitutes the Hebrew Bible's first and most authoritative section. These texts hold a central place in Jewish legal tradition, serving as the foundational source for virtually all Jewish law.

Historically, during the Second Temple Period (516 B.C.E.-70 C.E.), the Torah was the primary, and likely only, text taught to children receiving formal education. According to religious tradition, Moses, believed to have lived in the 13th century B.C.E., authored these books.

The first recorded challenge to this traditional attribution came from the 12th-century Jewish scholar Ibn Ezra. To avoid hostile criticism, he alluded subtly to several passages in Genesis and Deuteronomy that seemed to reflect a perspective much later than that of Moses.

This early example of the historical-critical method (an academic approach to studying the Bible that analyzes the historical context, authorship, and original meaning) laid the groundwork for later scholarly investigation, especially during the 19th century, which saw a surge in critical biblical studies.

The rise of the Enlightenment brought a more rigorous application of the historical-critical method, leading scholars to recognize the complexities behind the origins of the Pentateuch. German scholar Julius Wellhausen introduced the “Documentary Hypothesis,” proposing that the Pentateuch was composed of four distinct sources: the Jahwist ("J"), Elohist ("E"), Deuteronomist ("D"), and Priestly ("P").

According to Wellhausen, these sources were written between the 10th and 5th centuries B.C.E. and later combined into the text we have today.

Did You Know? Marie-Joseph Lagrange: A Great Scholar the Catholic Church Tried to Silence

Marie-Joseph Lagrange (1855-1938) was a Dominican priest, a pioneering Biblical scholar, and the founder of the renowned École Biblique in Jerusalem. Despite his significant contributions to biblical scholarship, the Catholic Church has been dragging its feet on his beatification initiated 30 years ago. Why the delay? Because Lagrange was, in a sense, "martyred" by his Church, accused of “modernism”, and forbidden from researching, writing, publishing, and teaching.

What was his crime? Lagrange applied a new scientific and critical approach to the Bible, challenging the traditional authorship of the Pentateuch. This bold stance didn’t sit well with the Church authorities of his time. Eventually, they ordered him to cease his research on the Hebrew Bible, Moses, and the Pentateuch, redirecting his focus to the New Testament.

However, as our understanding of Biblical studies has evolved, so has the collective memory of Father Lagrange and his work. Once condemned and punished, his methods are now widely accepted and employed by Catholic scholars. How the tables have turned!

In the late 20th century, scholars began to critique and refine the Documentary Hypothesis, favoring a more nuanced approach that viewed the Pentateuch as the product of several centuries of composition and redaction, reaching its final form in the 5th century B.C.E.

Despite these advancements, it’s crucial to acknowledge that all theories regarding the dating of the Pentateuch remain hypothetical. As R. Norman Whybray aptly notes in his book The Introduction to the Pentateuch:

“The debate is likely to continue indefinitely, and whether a new consensus will eventually emerge is far from certain. It would therefore be premature to attempt either an assessment of the present situation or a prognostication of the future... We are dealing entirely with hypotheses and not with facts. Proof, either in the mathematical or in the logical meaning of that word, will never be attainable.”

While we may never attain absolute certainty about the origins of the Pentateuch, the insights gained through critical scholarship have justifiably rejected the traditional (religious) attribution.

The Book of Isaiah

The Book of Isaiah places the prophet in Jerusalem during a critical period in Israel's history. He witnessed the Assyrian Empire's conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel and the subsequent overrunning of most of the kingdom of Judah.

Despite the widespread devastation, King Hezekiah and the city of Jerusalem managed to survive, with Isaiah present during these events, as described in the Book of Kings. This situates the prophet's activity roughly between 720 and 700 B.C.E. and suggests Isaiah wrote his book at the end of the 8th century B.C.E.

However, the narrative within the Book of Isaiah takes a notable shift after chapter 39. As early as the 12th century C.E., rabbis observed that Isaiah the prophet wasn’t mentioned after this point, and the context of the text appears significantly different.

This observation laid the groundwork for later scholarly inquiry. Starting in the 18th century, biblical scholars proposed that chapters 40 to 55, known as Deutero-Isaiah, were authored by a different writer during the Babylonian exile in the 6th century B.C.E.

This insight led to the understanding that the Book of Isaiah isn’t the work of a single individual writing at one time and place. Instead, it reflects a compilation of writings from different periods, contributing to a long and complex history.

Margaret Baker, in Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, encapsulates the scholarly consensus:

“The theory which eventually emerged was that the first section (chs. 1-39) consisted of the oracles of Isaiah in Jerusalem in the period 750-700 B.C.E.; the second (chs. 40-55, Deutero-Isaiah) came from an unknown prophet in exile in Babylon, and the third (chs. 56-66, Trito-Isaiah) was a postexilic work. The date suggested for this final 'Isaiah' varied between the late sixth century and the third-century B.C.E.”

The Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel stands out within the Hebrew Bible for its unique apocalyptic genre. It’s the only book of the Hebrew Bible that completely fits within that category. Apocalyptic literature reveals divine secrets and prophecies about the end times and it’s often full of visions and symbolic imagery.

Traditionally, The Book of Daniel has been attributed to the prophet Daniel, who allegedly lived during the Babylonian exile in the 6th century B.C.E.

According to this view, Daniel, a young Jewish exile of noble birth, rose to prominence in the Babylonian court due to his ability to interpret dreams and visions, which were seen as divine revelations.

However, contemporary scholars have challenged this traditional attribution, proposing instead that the Book of Daniel was composed in the 2nd century B.C.E., specifically around 165 B.C.E. This shift in dating is primarily based on linguistic, historical, and thematic evidence.

The detailed prophecies found in the later chapters of Daniel support this dating due to the accurate descriptions of events leading up to the reign of the Hellenistic king Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

The specificity and accuracy of these prophecies suggest they were written after the events had occurred, a technique known as “Vaticinium ex eventu” (“prophecy after the fact”).

Moreover, the accuracy of Daniel’s prophecies sharply diminishes after 165 B.C.E., further supporting the hypothesis that the book was written during this period.

For example, the detailed predictions in chapters 11 and 12, which precisely outline the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes and his persecution of the Jews, become increasingly inaccurate when describing events beyond that time.

Specifically, the text predicts the death of Antiochus IV in Palestine and the subsequent liberation of the Jewish people — events that didn’t occur as prophesied. Antiochus IV died in Persia in 164 B.C.E., and the Jewish people didn’t experience the immediate deliverance foretold in the text.

Referring to the contrast between traditional dating and the opinion of contemporary scholars, John J. Collins, in his book Daniel: With an Introduction to Apocalyptic Literature, notes: “Here it must be said that the evidence of the genre creates a great balance of probability in favor of the critical viewpoint... The most probable time of the composition of these stories is the third or early second-century B.C.E.”

Having examined a few notable examples from the Old Testament in our exploration of the Bible in chronological order, we now shift our focus to the origins of Christianity and the composition of the New Testament documents. Let's delve into the historical context and dating of these foundational texts.

Dating the New Testament Books in Order: A Few Notable Examples

In the section on the New Testament, we begin with the Gospels and take two outstanding examples (Mark and John). If you want to know more about how scholars date all four gospels, I recommend another article written by my colleague Keith!

The Gospel of Mark

The Gospel of Mark is generally considered the earliest of the four canonical gospels. While tradition holds that the author was a companion of Peter named Mark, critical scholarship has largely rejected this claim. Instead, most scholars believe an anonymous Christian author, likely living outside of Palestine, wrote the earliest Gospel several decades after Jesus' death.

In his Introduction to the New Testament, Delbert Burkett notes: "Most scholars date the Gospel of Mark to the period shortly before or after the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 C.E. This dating is based on Mark 13, which describes events connected with the Roman siege of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple. Here the evangelist describes either events that had already happened or events that he expected to occur shortly."

The detailed account in Mark 13 of the Roman siege and the subsequent destruction of the Temple strongly suggests the author was writing during or shortly after these events.

Moreover, an intriguing feature in Mark 13:14 further supports this dating. The verse includes an odd phrase, “let the reader understand,” which many scholars interpret as an indication that the author was referring to well-known contemporary events.

In other words, this note was probably a call for the audience to recognize and interpret the signs of their times — specifically, the destruction of the Temple that occurred in 70 C.E. These little clues reinforce the argument that the Gospel of Mark was composed around that time, either during or immediately after the siege of Jerusalem.

The Gospel of John

Unlike the Gospel of Mark, the Gospel of John is widely considered to be the last of the canonical Gospels written. Traditionally, the Church attributed this Gospel to the apostle John, son of Zebedee. However, virtually all modern scholars reject this attribution, determining, instead, that he was a low-class fisherman from the rural area of Galilee.

Furthermore, the Acts of the Apostles explicitly state that both John and Peter were "unlettered" (Acts 4:13), meaning they lacked the formal education necessary for crafting such a sophisticated and complex narrative. Therefore, as explained in our earlier article, the real author was likely an anonymous Christian living outside of Palestine.

Several factors support dating the Gospel of John to the end of the 1st century. Firstly, the theological development within the text suggests a later composition. Unlike the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), which emphasize the imminent return of Jesus, John presents a more developed Christology (the field of study concerned with the nature and role of Christ) with a substantial decrease in apocalyptic themes.

This shift indicates a period of reflection and theological development within the Christian community that likely occurred after the delay of the parousia (the second coming of Jesus). Additionally, the Gospel of John addresses the expulsion of Christians from the synagogue, a significant event that probably took place towards the end of the 1st century (John 9:22, 16:2).

Epistle to the Romans

Paul's Epistle to the Romans stands out as one of his most significant writings, offering what is often considered his most systematic theological exposition. Unlike his other letters, which typically address specific issues within early Christian communities, Romans was written to lay out Paul's theological insights from a broader perspective.

Determining the exact date of this epistle involves piecing together various historical clues. Most contemporary scholars agree that Paul wrote Romans during the winter of 56/57 C.E. This conclusion is drawn from several interconnected pieces of evidence.

For those interested in delving deeper into the evidence and scholarly analysis surrounding the dating of Romans, we invite you to explore our detailed article on this topic. There, we provide a thorough examination of the clues and historical context, presented in a scholarly yet accessible manner.

Pastoral Epistles: Epistle to Titus

The Epistle to Titus is part of the Pastoral Epistles — a collection that includes 1 and 2 Timothy. These letters are considered a unified corpus.

As Norbert Brox notes in Die Pastoralbriefe:

“Their uniformity and cohesion are further documented in detail by a close affinity in language (style, vocabulary), content, and the assumed church-historical situation. They speak the same elevated Greek, live in the same theological conceptual world, combat the same heresies, and generally know the same organization and constitution of the individual churches. Therefore, characterization and interpretation, as well as the resolution of their problems, can only be given for all three Pastoral Letters together.” (my translation)

Scholars date the Epistle to Titus to the end of the 1st century or even the beginning of the 2nd century for several reasons:

So, while tradition attributes the Epistle to Titus to Paul, critical scholarship rightly places its composition at the end of the 1st century or the beginning of the 2nd century. Let’s now take a look at our last New Testament example.

1 Peter

The author of 1 Peter identifies himself as “Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ” (1:1). However, most scholars doubt this claim for several reasons. Firstly, the author demonstrates an excellent command of the Greek language. It’s doubtful that a fisherman from Galilee, described in Acts as unlettered, could have composed such a sophisticated narrative.

While it’s theoretically possible that Peter could have received years of education after Jesus' death, this scenario seems improbable. There are no analogous examples from the ancient world of someone transforming from an illiterate fisherman to a highly educated writer.

Additionally, the letter indicates that Christianity had spread to Gentiles in the provinces of Bithynia-Pontus and Cappadocia (1:1). This suggests that the epistle was written after the time of Paul.

Bart Ehrman, in his study Forgery and Counterforgery, concludes: “It is widely held today that the book wasn't written by Simon Peter...This is the general opinion among critical scholars, outside the ranks of those who disallow forgery in the New Testament on general principle.”

Based on internal evidence, scholars argue that 1 Peter was written somewhere between 70 and 100 C.E. Delbert Burkett provides further context:

“Within the period 70-110 C.E., plausible dates would be the reign of Domitian (81-96 C.E.) when the Book of Revelation also calls Rome 'Babylon' and indicates a conflict with Rome in the province of Asia, or the reign of Trajan (98-117 C.E.) when we have evidence of Roman persecution of Christians in Bithynia-Pontus.”

Finally, this timeline aligns with the spread of Christianity to the regions mentioned in the epistle and the socio-political context of increased Roman hostility towards Christians.

Conclusion

In exploring the chronological order of the Bible, we've delved into the complex history behind some of its most significant texts. From the mysterious origins of the Pentateuch and Isaiah to the apocalyptic visions in Daniel, understanding the true order of the Bible requires careful scholarly investigation.

We've also examined several New Testament writings such as Mark, John, Romans, Titus, and 1 Peter to uncover the historical context and dates. We’ve seen how scholarly opinions differ substantially from the tradition of the Church.

This journey through the Bible in chronological order is just the beginning. While we've provided a broad overview, the dating of each book is way beyond the scope of this article.

But don’t worry! We plan to delve deeper into the dating of each Bible book in future articles, thus offering a comprehensive resource for those seeking to understand the complex history of the texts that have shaped the culture of the Western world.

For those interested in a deeper exploration of biblical origins, consider enrolling in Bart D. Ehrman's online course, “In the Beginning: History, Legend, and Myth in Genesis.” Dr. Ehrman provides a scholarly look at the Book of Genesis, revealing how contemporary historians and archaeologists interpret intriguing topics such as the 7-day creation and the story of Noah and the flood.

FREE COURSE!

WHY I AM NOT A CHRISTIAN

Raw, honest, and enlightening. Bart's story of why he deconverted from the Christian faith.

Over 6,000 enrolled!