Jewish Diaspora: Map, Timeline, and Why the Exile Occurred

Written by Joshua Schachterle, Ph.D

Author | Professor | Scholar

Author | Professor | BE Contributor

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Verified! See our guidelines

Edited by Laura Robinson, Ph.D.

Date written: September 4th, 2024

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

The Jewish diaspora is a profound and enduring part of the history of the Jewish people, illustrating a journey marked by suffering, adaptation, and resilience.

In this article, I’ll explore the origins and evolution of the Jewish diaspora, tracing its roots from ancient exiles to modern communities. I’ll also provide a timeline of key events that contributed to this widespread dispersion and discuss why the exiles occurred. With a detailed map and historical analysis, I’ll offer a clear understanding of how the Jewish diaspora unfolded and its enduring impact on Jewish culture and identity.

What Is the Jewish Diaspora?

Diaspora (pronounced die-AS-pora) is a Greek word which simply means “scattering” or “dispersion.” However, in the Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World, Melvin Ember, Carol Ember, and Ian Skoggard note that, for many years, the word has referred specifically to populations spread across territories separate from the places they originated. (Affiliate Disclaimer: We may earn commissions on products you purchase through this page at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our site!) In this sense, there are many diasporas in the world, including the Indian diaspora, the Mexican diaspora, and the Chinese diaspora. In this article, though, I’ll focus specifically on the Jewish diaspora.

In his article “Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return,” William Safran outlines several rules to differentiate diasporas from migrant communities. The most important of these is that the diaspora population maintains a collective myth of their homeland, which they consider their true home, no matter how long they have been separated from it.

Safran also defined diasporas as people forced into exile by political or economic factors. In other words, the terms “exile” and “diaspora” are synonyms for him. However, I think it makes more sense to think of a diaspora, as a larger category, resulting from one or more forced exiles.

Nevertheless, in Global Diasporas, social scientist Robin Cohen differs slightly from Safran’s opinion, arguing that unlike exiles, members of a diaspora group can also leave their homeland voluntarily and assimilate willingly into a new culture. As we’ll see, both definitions apply to the Jewish diaspora.

By the way, the term diaspora occurs three times in the New Testament. In James 1:1, the author addresses his letter “To the twelve tribes in the diaspora.” 1 Peter 1:1 addresses itself to “To the exiles of the diaspora in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia.” This shows that, even in the late 1st century CE, the term was used to refer to Jews outside Palestine. Finally in John 7:35, the Jewish religious leaders wonder where Jesus is going to go: “Does he intend to go to the diaspora among the Greeks and teach the Greeks?”

The term can also be found several times in the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible. It's clear, then, that the notion of the Jewish diaspora occurred very early in Jewish history and thought.

Why Did the Jewish Diaspora Occur and When?

The beginning of the Jewish diaspora can be traced to the 8th century BCE when what we now think of as Israel was actually two kingdoms: Israel in the north and Judah in the south. In what came to be known as the Assyrian exile, an Assyrian king named Tiglath-Pileser III began expelling Israelites from the Kingdom of Israel in 733 BCE. Then, in 722 BCE, the Assyrian king Sargon II completely subjugated the Kingdom of Israel and forcibly deported thousands of Israelites, sending them to Mesopotamia. The northern kingdom of Israel would never recover.

Next came the Babylonian exile in the 6th century BCE. While the kingdom of Judah remained after the northern kingdom of Israel had been destroyed, the Babylonians, under their king Nebuchadnezzar II, conquered Judah in 586, and again in 597 BCE, deporting most of the elites of Judah to Babylonia. In his History of the Jewish People: The Second Temple Era, Hersh Goldwurm writes that after this conquest, the Judahite or Jewish population came to occupy two main geographical locations, Babylonia for those who had been captured, and Israel — now defined as the northern and southern kingdoms — for those left behind.

When the Babylonians were later conquered by the Persians under their king Cyrus the Great, in 539 BCE, any Jews who wanted to return to their homeland and rebuild were allowed to do so. Many of them did, rebuilding Jerusalem and the Temple, but many others remained in Babylonia.

Meanwhile, the Jewish historian Josephus, claimed that Alexander the Great’s successor Ptolemy I conquered Israel in 322 BCE, forcing 120,000 Jewish captives to Egypt. Many other Jews would later move from Judah to Egypt of their own free will. Ptolemy apparently settled the Jews in Egypt to employ them as mercenaries.

So while some Jews had returned to Israel and rebuilt the Temple (hence the name of this era: The Second Temple Period from 516 BCE to 70 CE), many remained in Babylonia and Egypt. For instance, in The Jews under Roman Rule, Mary Smallwood notes that, in the 1st century BCE, the Greek geographer and historian Strabo wrote that Jews were one of the four largest population groups living in the city of Cyrene, in what is now Libya.

When Pompey the Great of Rome conquered Jerusalem in 63 BCE, effectively annexing Israel as part of the Roman Empire, the diaspora expanded due to people escaping from Rome’s draconian military. When Rome laid siege to Jerusalem, finally destroying it in 70 CE, Mary Smallwood writes that Rome sold many Jews into slavery in many different regions. In addition, the upsurge in voluntary Jewish emigration from people escaping the wars caused a drop in Palestine's Jewish population.

In Diaspora: Jews amidst Greeks and Romans, Erich Gruen writes that, not unlike the situation in the Babylonian exile, the destruction of Jerusalem by Rome forced many displaced Jews to frame a new self-definition and adapt to the likelihood of an indeterminate time of exile.

As an example of this adaptation, we have the apostle Paul, a Greek-speaking Jew from Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). Paul lived in the 1st century CE before the destruction of the second Temple, but we can assume that his family had been there for at least a generation by the time he was born.

If you’re interested in the history, legends, and myths of Israel in the Hebrew Bible, you might like Bart Ehrman’s online class “In the Beginning.” Furthermore, Bart has another online class called “Finding Moses” about the specific history and myth behind this heroic biblical figure.

Well-Known Jewish Diaspora Groups

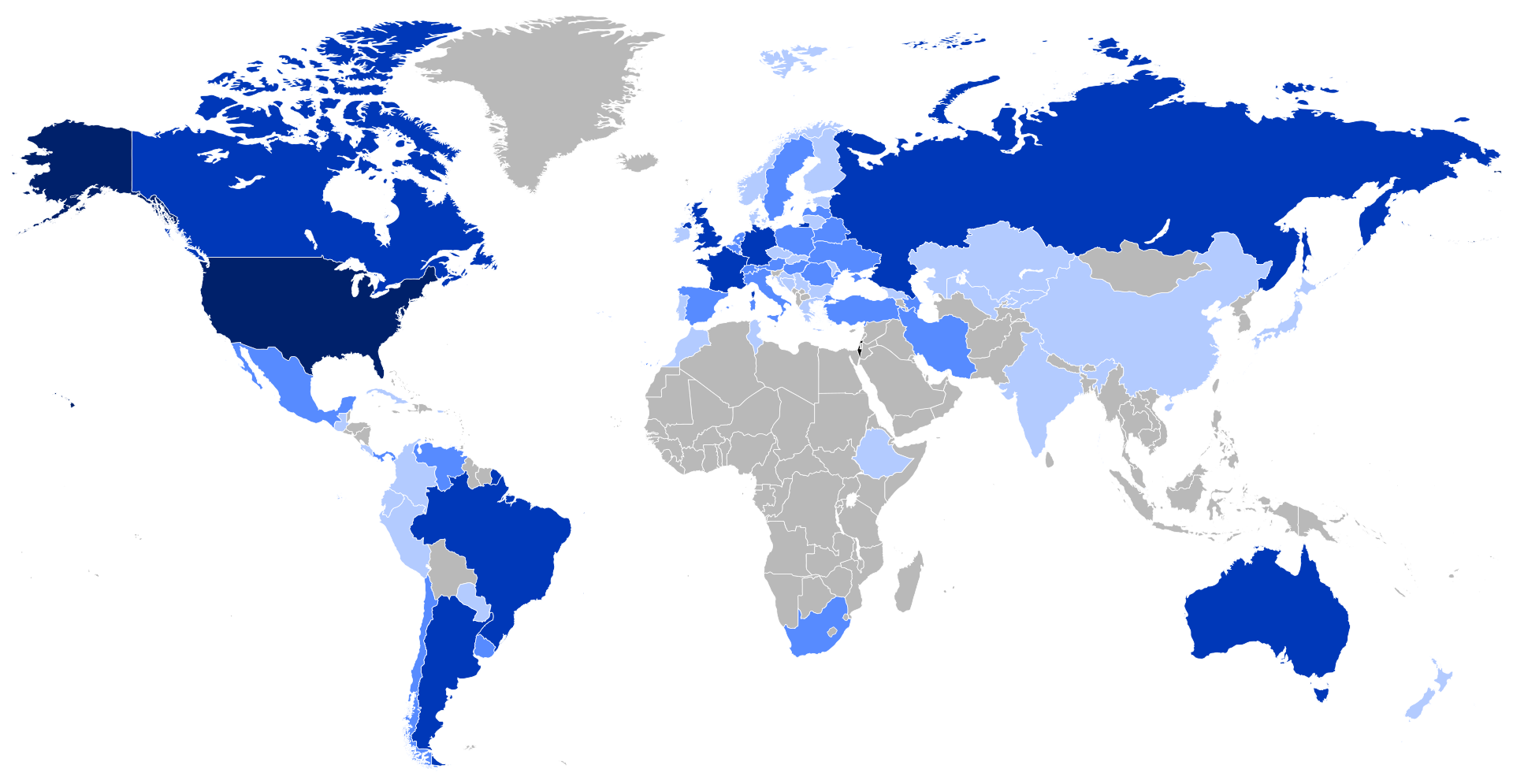

These trends of conquest, exile, and voluntary emigration would continue throughout the Middle Ages. Some Jewish populations immigrated to what is now Germany and northeastern France. These came to be known as Ashkenazi Jews. They also developed their own distinct language called Yiddish. Unfortunately, because of the regions in Europe where they lived, the vast majority of Jews later killed in the Holocaust were Ashkenazi. Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud were both Ashkenazi Jews.

Sephardic Jews, on the other hand, moved to the Iberian Peninsula, either Spain or Portugal. They were forcibly expelled from Spain by Queen Isabella in 1492 and migrated, some to North Africa, and others to the Netherlands, Britain, France, and Poland. One of the best-known Sephardic Jews was Maimonides, a medieval Jewish philosopher who was very influential as a rabbi and Torah scholar.

Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews were the largest groups of European Jews. However, there were many other Jewish groups in the diaspora, which I’ll look at next.

Source: Map of the Jewish Diaspora of the World by Allice Hunter, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

More Jewish Diaspora Groups

Mizrahi Jews are the descendants of Jewish communities that never left the Middle East, living in countries such as Iraq, Iran, Yemen, Morocco, and Egypt. Jews remaining in those countries still speak Arabic or a Judeo-Arabic dialect. Those who relocated to the modern state of Israel speak modern Hebrew. Well-known Mizrahi Jews include the medieval philosopher and rabbi Saadia Gaon and Nobel Prize-winning author Shlomo Ibn Gabirol.

Beta Israel is an Ethiopian Jewish community that still employs many ancient Jewish practices and traditions. Many of them immigrated to Israel during Operation Moses (1984) and Operation Solomon (1991), two covert Israeli military operations to airlift Ethiopian Jews from Ethiopia and Sudan to Israel. Israeli politicians Shlomo Molla and Avraham Neguise are members of this group.

Bene Israel is a Jewish community in India. They claim their ancestors settled there centuries ago but this is difficult to prove. They are now mostly concentrated around the city of Mumbai. Well known members of Bene Israel include poet Nissim Ezekiel and judge Elijah Moses.

Romaniote Jews are a population of Greek Jews and one of the oldest European Jewish populations. They speak a Greek dialect called Yevanic, which also contains Hebrew. Sadly, most of them were murdered during the Nazi occupation of Greece, and the majority of survivors relocated to Israel. Byzantine poet Eleazar birabbi Qallir and Sabbatai Zevi, who claimed to be the Jewish messiah in the 17th century CE, were both Romaniote Jews.

Karaite Jews came originally from Persia and Iraq but now have communities in Egypt, Crimea, and Israel. They follow a unique form of Judaism that relies solely on the Hebrew Bible, and completely denies the authority of later rabbinic tradition. Caleb Afendopolo, a 15th-century scholar of many subjects, was a Karaite Jew.

Mountain Jews have lived in the Caucasus in countries such as Azerbaijan and Dagestan for centuries, maintaining their own distinct language called Judeo-Tat, a Judeo-Persian dialect. Their ancestors may have originated from ancient Persia in the 5th century BCE. Their religious traditions included a commitment to the Jewish mysticism of the Kabbalah. Israeli singer Omer Adam is descended from Mountain Jews.

Conclusion

The Greek word diaspora originally meant a scattering (of anything). In the case of the Jewish diaspora, this is an apt term. Beginning in the 8th century BCE, Jews in Israel were conquered and deported from their homelands over and over for centuries by foreign empires. While some were captured and forcibly moved during the Assyrian and Babylonian captivities, for example, others went elsewhere to escape wars or the possibility of being sold into slavery.

The result of this was that Jews eventually spread all over the world, taking their customs and religion with them, although in different countries, these customs would become regionally modified. Thus, the diaspora caused the spread of Judaism all over the world.

Today, there are Jewish communities in every corner of the globe. While the modern state of Israel was established in 1948, there are still far more Jews living outside that traditional homeland than in it.