Arianism: What is the Arian Heresy in Christianity?

Written by Marko Marina, Ph.D.

Author | Historian

Author | Historian | BE Contributor

Verified! See our guidelines

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Date written: October 22nd, 2025

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

Have you ever heard about Arianism? In preparing a recent class on power and violence in the Middle Ages, I found myself immersed in the inquisitorial records of Bishop Jacques Fournier, and the meticulous notes of trials he conducted in a small corner of 14th century Southern France.

As I read through these cases, I was struck not only by the precision of the questioning but by the number of voices we no longer hear. For every testimony preserved, countless others were silenced, lost through suppression, fear, or the accidents of transmission.

This imbalance of surviving sources is hardly unique to the Middle Ages. It’s just as true for the earliest centuries of Christianity, where the “heretical” and “unorthodox” were often remembered only through the writings of those who opposed them.

Yet even through this one-sided lens, faint echoes of alternative Christianities remain. Before the triumph of what later became “orthodoxy,” the movement was a patchwork of communities and convictions, each struggling to define who Jesus was and what it meant to worship the one God.

The boundaries that later seemed fixed were, in their own time, fluid and fiercely contested. These early debates weren’t abstract theological exercises but living questions that shaped how believers prayed, organized, and understood salvation itself.

Among the most consequential of these forgotten or marginalized currents was what history has come to call Arianism, a movement that, for a time, commanded the allegiance of emperors, bishops, and entire regions of the Christian world.

Long reduced to the label of “heresy,” it nevertheless represents one of the most important turning points in the effort to define the relationship between Jesus and God.

However, to understand how such a controversy could divide the ancient Church and eventually transform its doctrine, we must first return to the diverse world of early Christianity from which Arianism emerged.

Arian Heresy Within the Broader Early Christian Diversity

To understand Arianism, we must first understand the social and religious world from which it emerged. And that world can be defined by one word: diversity — or, more accurately, by two words: radical diversity. The first centuries of Christianity were marked by a stunning variety of beliefs, practices, and scriptures.

There was no centralized authority, no universally recognized creed, and no fixed canon of sacred writings.

In his bestselling book Lost Christianities, Bart D. Ehrman encapsulates this diversity, noting:

(Affiliate Disclaimer: We may earn commissions on products you purchase through this page at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our site!)

In the second and third centuries there were Christians who believed that Jesus was both divine and human, God and man. There were other Christians who argued that he was completely divine and not human at all. (For them, divinity and humanity were incommensurate entities: God can no more be a man than a man can be a rock.) There were others who insisted that Jesus was a full flesh-and-blood human, adopted by God to be his son but not himself divine. There were yet other Christians who claimed that Jesus Christ was two things: a full flesh-and-blood human, Jesus, and a fully divine being, Christ, who had temporarily inhabited Jesus' body during his ministry and left him prior to his death, inspiring his teachings and miracles but avoiding the suffering in its aftermath.

Ehrman’s summary captures what modern historians continue to emphasize: the earliest Christian movement wasn’t a single, unified body but a mosaic of competing interpretations of Jesus’ identity and mission.

Some groups, such as Marcion and his followers, rejected the Jewish Scriptures altogether, seeing the God of the Old Testament as inferior to the God revealed by Jesus. Others, including a variety of Gnostic communities, produced intricate mythologies describing multiple divine realms, fallen powers, and the human soul’s path back to the ultimate source.

If you’d like to dive deeper into these fascinating early movements and discover how their ideas once rivaled what became mainstream Christianity, you should explore Bart D. Ehrman’s course Earliest Christian Heresies.

In 8 captivating lectures, Dr. Ehrman uncovers the lost beliefs, rival gospels, and theological battles that shaped the earliest centuries of the faith. Learn about the silent voices of Christian history (those marginalized for centuries) and encounter a side of early Christianity as diverse, surprising, and thought-provoking as the one the winners preserved.

Each of these groups considered itself authentically Christian, tracing its lineage to Jesus’ first followers and claiming to preserve the true understanding of the divine. Their opponents were always the ones who had gone astray.

In that volatile landscape, what later became known as “orthodoxy” was only one of many voices contending for legitimacy.

To put it more bluntly, the distinction between “orthodoxy” and “heresy” didn’t exist from the beginning. Rather, it was the outcome of sustained polemical battles, inherited advantages, and institutional consolidation.

“Orthodoxy and heresy” are, as Nicol D. Lewis notes, “emic terms, labels developed only within a social group. In other words, many people might have considered themselves to be orthodox and others, heretics. The terms are subjective and therefore not very useful.”

In any case, recognizing this rich and often turbulent diversity is essential for grasping the origins of Arianism. The Arian controversy didn’t appear in a vacuum. It was the product of centuries of debate about the nature of Christ and his relationship to God.

So, before we can define Arianism precisely or trace its historical development, we need to examine those Christological battles that animated the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th centuries — disputes over how the divine and the human could coexist in the person of Jesus.

Who Was Jesus? Christological Battles as Preludes to the Emergence of Arianism

Every Christological debate and polemic that marked the early centuries of Christianity ultimately traces back to the dual character of the New Testament writings themselves.

Within these foundational texts, readers encounter, on the one hand, a profoundly human Jesus, a figure who eats, sleeps, weeps, and prays; who is born, baptized, and executed under Roman authority. He has disciples, friends, opponents, and a family.

In many ways, he resembles other Jewish prophets and teachers who roamed 1st-century Palestine proclaiming some version of the apocalyptic message.

Yet, within the same collection of writings, we also find affirmations that Jesus was far more than human. The infancy narratives in Matthew and Luke already hint at divine origins; the Gospel of John proclaims that “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us.”

The language of the New Testament therefore holds together two convictions with equal force (Jesus as fully human and yet, in some sense, divine) creating a tension that could generate sharply different theological emphases in the centuries that followed.

These affirmations point to what Luke T. Johnson has aptly called, “the paradoxical character of the first Christian experience.” The earliest believers were convinced that, in Jesus, they had encountered both God’s decisive revelation and a genuine human being, yet they struggled to articulate how these two dimensions cohered.

The pendulum swings of emphasis point to the impossibility of rendering the experience adequately in linguistic formulae. The problem wasn’t merely semantic. Far from it! It lay at the heart of Christian identity.

To confess that Jesus was both divine and human raised profound questions about God’s unity, the meaning of salvation, and the very boundaries of monotheism inherited from Judaism.

Did You Know?

A Bishop with More Comebacks than a Rock Star.

If something (or someone) illustrates the shifting tides between “orthodoxy” and Arianism; between Church and Empire, it’s Athanasius of Alexandria and his remarkably turbulent life. Famous for the slogan Athanasius contra mundum (“Athanasius against the world”), he somehow managed to be deposed and exiled 5 separate times by 4 different emperors.

Each emperor’s decision depended on which theological faction (Nicene or Arian-leaning) held the upper hand at the moment. One decade he was the empire’s defender of the true faith; the next, he was a troublemaker accused of disturbing the peace. Few bishops in history have packed so many comebacks into a single career.

During his exiles, Athanasius didn’t sit idle. At one point, he hid among Egyptian monks and desert ascetics, writing letters, rallying supporters, and sharpening his image as a persecuted hero.

From these periods of retreat emerged one of the most effective public-relations campaigns of the ancient world: Athanasius turned his repeated downfalls into proof of his righteousness. By the time of his death in 373 C.E., his reputation as the immovable defender of orthodoxy was secure, though, ironically, the Arian controversy that defined his life would continue for generations after him.

These pendulum swings of emphasis began almost immediately after Jesus’ death and only intensified as Christianity spread across the Greco-Roman world.

Some communities stressed his divine nature so strongly that his humanity appeared illusory, a position later labeled Docetism. Others, emphasizing his genuine human life, argued that his divine status was something bestowed upon him by God at a certain point in his life — an Adoptionist view.

Into this long and complex history entered a modest priest from Alexandria named Arius, whose teaching would ignite one of the fiercest controversies the Christian world had ever seen. His attempt to make sense of Jesus’ relationship to God (to define how the Son could be divine without compromising the Father’s supremacy) set off decades of theological and political turmoil that would culminate in the Council of Nicaea — commonly misspelled “Nicea.”

The debate that followed gave rise to what history remembers as Arianism, a movement that forced the Church to clarify, with unprecedented precision, what it meant to call Jesus both God and man.

So, let us now turn to this pivotal figure and ask: Who was Arius, and what was Arianism really about?

The Emergence of Arianism: Arius and the Alexandrian Controversy

The traditional story of Arius is well known and has been told for more than 1500 years. According to this picture, Arius was a presbyter in the city of Alexandria, a learned but stubborn man who taught that the Son of God was a created being, not eternal like the Father.

His slogan, as later remembered by his opponents, was said to be “there was a time when the Son was not.”

In this account, Arius demoted Jesus to a subordinate, semi-divine status, greater than the rest of creation but less than God. The controversy that erupted around him was presented as the Church’s first great internal crisis, forcing bishops across the empire to define the doctrine of the Trinity.

The image of Arius that passed into ecclesiastical memory was that of a calculating heretic, an intellectual troublemaker whose teachings threatened to unravel the unity of the Christian faith.

In this long-established interpretation, Arius became the archetypal villain of Christian history. Later theologians and Church historians, relying on Athanasius of Alexandria’s impassioned polemics, portrayed him as the originator of a heresy so grave that it nearly destroyed Christianity from within.

His theological followers (the so-called Arians) were even depicted as deniers of Jesus’ divinity and corrupters of the Gospel message. Within this framework, the Council of Nicaea in 325 C.E. appeared as the decisive triumph of orthodoxy over heresy, the moment when the true faith was preserved from the dangerous speculations of one misguided priest.

Yet, as contemporary historians have increasingly recognized, this narrative wasn’t the product of neutral reporting but of 4th-century polemical battles in which theological disagreement and personal rivalry became intertwined.

Recent scholarship has moved decisively away from this simplified portrait. As Marilyn Dunn and others have argued, the traditional picture of Arius owes more to Athanasius’ rhetorical construction than to Arius’ own writings or intentions.

The historical Arius, Dunn reminds us, wasn’t an innovator seeking to downgrade Jesus but a conservative priest attempting to defend what he saw as the integrity of Christian monotheism.

His surviving letters show a man deeply concerned about language that blurred the distinction between Father and Son, fearing that such formulations came dangerously close to the emanationist theologies of Valentinian Gnosticism and the dualistic cosmology of Manichaeism, two popular and competing movements in his day.

Arius’ opposition to the term homoousios (“of the same substance”) stemmed from his desire to avoid any notion that the Son was a physical extension or portion of the Father’s being, an idea that, to him, echoed precisely those heresies the Church had long sought to reject.

In Dunn’s reconstruction, Arius was less a heretic than a pastor and popularizer, a man of learning and conviction who expressed complex theology in accessible forms.

He wrote hymns and theological songs collected under the title Thalia (a term meaning “banquet”) and may have set them to everyday melodies so that workers and travelers could sing them. This pastoral creativity, far from being subversive, was an attempt to engage ordinary believers in theological reflection.

Arius also appears to have mobilized women’s participation in his circle, perhaps as a deliberate counter to the influence of Manichaean and Gnostic female teachers in Alexandria. He emerges not as a revolutionary, but as a priest striving to preserve doctrinal clarity in a city known for its intellectual and spiritual ferment.

His teaching that the Son was begotten “before all ages” and through him all things were made underscores that, in Arius’ view, the Son’s divinity was real, though derivative, distinct from, and subordinate to the Father’s unique unbegottenness.

Dunn’s most striking claim is that Athanasius effectively “invented” Arianism as a coherent heresy.

After Arius’ death in 336 C.E., Athanasius (Alexander’s successor in the Alexandrian episcopate) fashioned a powerful narrative of orthodoxy under siege, casting himself as the defender of truth against the “Ariomaniacs.”

In his Discourses Against the Arians, he selectively quoted and reinterpreted Arius’ writings, portraying him as one who denied the Son’s divinity outright. Through Athanasius’ extraordinary literary and political influence, this image hardened into “orthodoxy’s” official memory.

The label “Arianism” came to designate a range of later theological positions that often bore little resemblance to what Arius himself had taught.

In Dunn’s reading, the controversy that bears his name was less about Arius’ own theology than about the power struggles, rivalries, and linguistic uncertainties that marked the Church’s effort to define the mystery of Jesus in philosophical terms.

Whether the traditional theory or Dunn’s more nuanced interpretation comes closer to the historical reality, it remains beyond doubt that the crisis surrounding Arius forced the Church to confront questions it could no longer avoid.

What did it mean to confess that Jesus was both divine and human? How could Christians speak of the Son as begotten without compromising God’s unity or eternity? The debate over these issues would soon move from the streets and churches of Alexandria to the imperial stage.

The first ecumenical council ever convened (in Nicaea in 325 C.E.) would take up these questions with the aim of producing an “official” response from the emerging “orthodox” Church to the challenge posed by Arius and his supporters.

Arianism at the Council of Nicaea and Beyond

Even before 325 C.E., theological and political battles over Arianism had spilled into the open, producing tangible consequences for communities across the eastern Mediterranean.

In 321 C.E., a local synod in Alexandria formally deposed Arius and his followers, accusing them of disturbing ecclesial unity and corrupting doctrine. Arius and several of his clergy fled eastward to Palestine, where they sought protection among sympathetic bishops, most notably Eusebius of Caesarea.

Other bishops, including Eusebius of Nicomedia, also expressed support for Arius, framing the dispute not as heresy but as a matter of legitimate theological interpretation. So, by the early 320s, the controversy had spread well beyond Egypt and became an empire-wide crisis.

Recognizing that piecemeal solutions (local councils, pastoral letters, and personal mediation) were no longer sufficient, Emperor Constantine decided to change course and organize an ecumenical council in Nicaea. His earlier attempts to reconcile the parties through correspondence and the intervention of his trusted advisor Ossius of Cordoba had failed.

Why did he change his strategy so dramatically? In her study The Early Church, Morwenna Ludlow provides some answers:

Some have suggested that Alexander, on receipt of Constantine’s letter, persuaded Ossius that the issues were far more serious than the emperor thought. Another factor may have been a large council at Antioch in 325 which produced a very clear-cut condemnation of Arianism and excommunicated three bishops, including the very influential Eusebius of Caesarea. Constantine must have realized the destabilizing force of such a move – despite the fact that the Antioch excommunications were provisional on further debate at a council planned for Ancyra later that year. Constantine may also have been aware that the bishop of his eastern capital Nicomedia was a prominent supporter of Arius. It is likely that it was Constantine who proposed that the council of Ancyra be moved to Nicaea and opened the invitation to all bishops.

In due course, the bishops gathered in Nicaea, a city conveniently located near the imperial residence in Nicomedia. Modern estimates place the number of attendees between 220 and 250, though later tradition inflated the figure to the symbolic “318.”

The council was presided over by Ossius of Cordoba, acting as Constantine’s ecclesiastical advisor, while the emperor himself presided ceremonially, lending imperial legitimacy to the proceedings.

The agenda was broad (ranging from the date of Easter to issues of church discipline) but the central and most divisive topic remained the relationship between the Father and the Son.

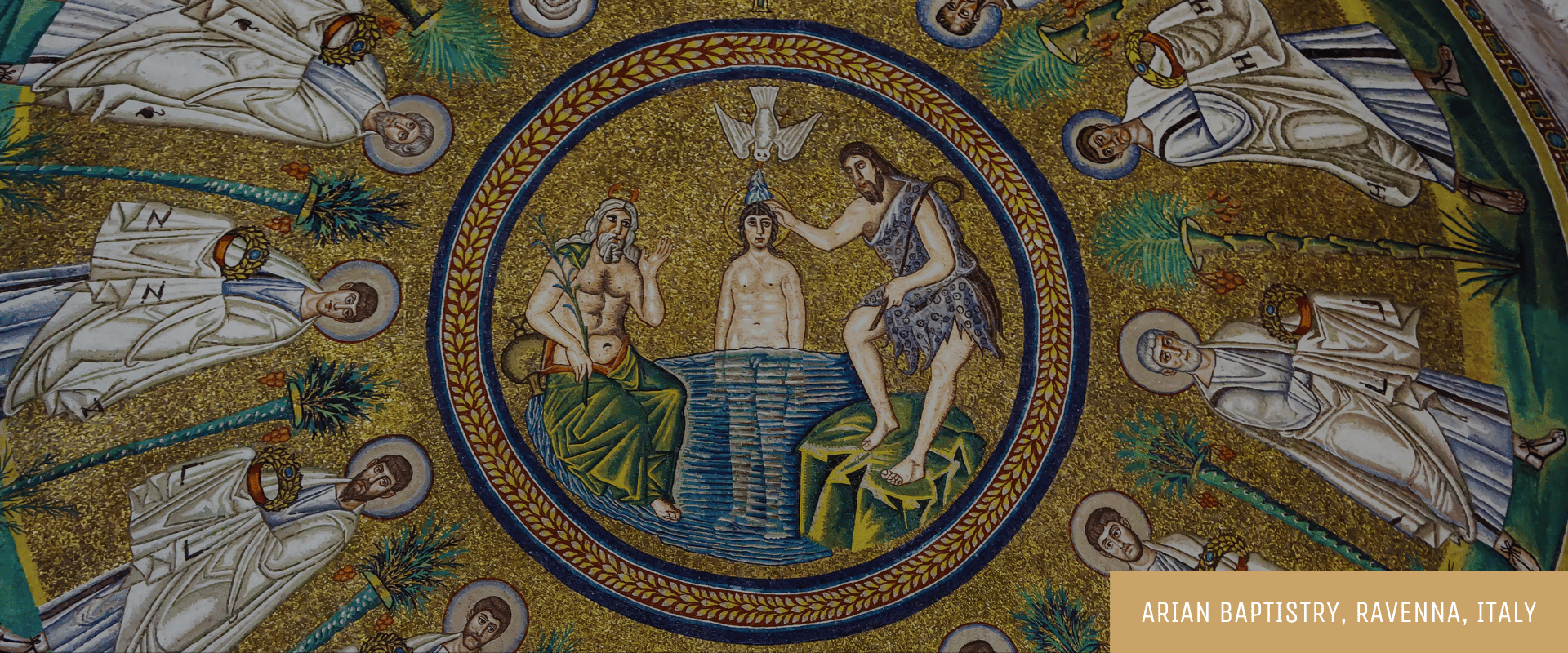

The assembled bishops debated terminology drawn from Scripture and philosophy, struggling to express how the Son could be divine without compromising monotheism. Eventually, the council produced the now-famous Nicene Creed, declaring the Son to be “begotten, not made, of the same substance (homoousios) as the Father.”

Arius, along with two Libyan bishops who refused to sign, was excommunicated and exiled, and his writings were ordered burned.

For the emperor, the council’s decisions represented the triumph of unity over division, but for the wider Church they inaugurated a new and long-lasting period of conflict. Despite Constantine’s endorsement of the Nicene Creed, many bishops found its philosophical language unsettling and its reliance on the word homoousios problematic.

In practice, the council had not resolved the theological question but relocated it: from Alexandria’s local churches to the entire Christian world.

Even Constantine himself began to waver in his enforcement of the creed. Within a few years, he recalled Arius from exile, and imperial policy shifted toward reconciliation. By the time of Constantine’s death in 337, the empire stood deeply divided, with competing interpretations of the Nicene formula already proliferating.

Under Constantine’s successors, Arianism revived with new force. His son Constantius II, ruling the eastern provinces, favored bishops sympathetic to Arius’ position and sought to impose a more moderate theology (often called Homoian) that avoided both the Nicene “same substance” and Arius’ alleged subordinationism.

Numerous regional councils, such as those at Antioch (341) and Sirmium (351), produced alternative creeds aimed at compromise, but, in effect, diluted Nicene terminology. In the West, bishops loyal to Nicaea protested these developments, while in the East, theological camps hardened around competing formulations: homoousios (“same substance”), homoiousios (“similar substance”), and anomoios (“unlike”).

The conflict’s persistence revealed how deeply Christology and imperial politics had become intertwined. Emperors used theological alignments to consolidate power, while bishops leveraged imperial support to advance ecclesiastical agendas.

Far from disappearing, Arianism continued to attract adherents well into the late 4th century, even after the Council of Constantinople (381) reaffirmed the Nicene position and expanded the creed to include the Holy Spirit.

So, the story of Arianism didn’t end with its official condemnation. Through missionary efforts among Germanic peoples (especially by Ulfilas (Wulfila), who translated the Bible into Gothic) Arian Christianity spread among the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and Vandals.

When these so-called “barbarian” tribes established kingdoms in the former Roman provinces of Gaul, Hispania, and North Africa, they brought their Arian faith with them. For several centuries, Arian and Nicene Christians coexisted uneasily in the post-Roman West.

Only in the late 6th century, after the conversion of the Visigothic King Reccared I to Catholicism in 589 C.E., did the last major Arian kingdom formally align with Nicene orthodoxy.

Conclusion

Whenever someone asks me why I chose to pursue a doctoral degree in early Christian history, I often point to Arianism and the whole array of Christian movements and beliefs that were almost forgotten.

In this article, we’ve seen how a single controversy surrounding a priest from Alexandria opened a window into the diversity, conflict, and creativity of the early Church.

What began as an attempt to explain how Jesus could be both divine and human turned into a centuries-long struggle that shaped the very boundaries of Christian “orthodoxy.” It’s a reminder that the history of Christianity isn’t a straight line of unbroken consensus, but a story of debate, change, and sometimes sheer human stubbornness in the face of mystery.

And that’s precisely what makes studying this period so compelling. Beneath the grand councils, imperial decrees, and theological treatises are people, believers trying to make sense of faith, identity, and power in a rapidly changing world.

The legacy of Arianism shows that “heresy” and “orthodoxy” weren’t fixed categories from the start but products of history, negotiation, force, polemics, and conviction. For me, that’s the heart of why early Christian history continues to fascinate.

What is Arianism? It’s an open invitation to explore the captivating world of the earliest Christians. More than 10 years ago, I accepted that invitation and I’m still glad that I did!